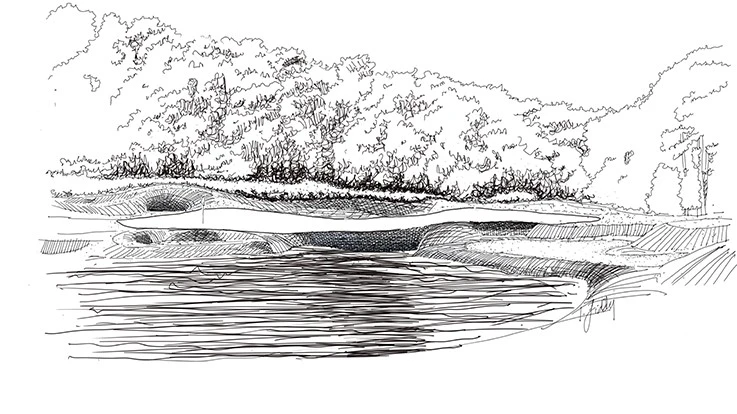

Sketch by Tim Liddy

What do superintends want? Less maintenance. What do architects want? Steep slopes adding contrast, more shadows typically adding to maintenance. The answer? Revetted bunkers using artificial turf.

What is a revetted bunker? The Merriam-Webster dictionary definition of revetment is: “a facing (as of stone or concrete) to sustain an embankment.” It comes from the French word “revetir,” which means “to put on, wear or don.”

The history of revetted bunkers starts in Scotland as a tool to stop wind erosion, to shore up the faces of deep bunkers when there was nothing else more practical. In golfing terms, a revetted bunker is one where sods (grass and the part of the soil beneath it held together by roots or a piece of thin material) are stacked to create a layered effect. Layers of sod have been used for this purpose for ages and have been a feature of Fife Golf since the 19th Century.

(CLICK HERE to read GCI’s January feature story on revetted bunkers.)

Greatly influenced by his visits to Scotland and early in my career with Pete Dye, we tried several times to build a revetted wall bunker on the 3rd green at Crooked Stick in Carmel, Ind. Our mistake was building the revetted wall using locally grown sod planted in heavy clay soils. The revetted wall would invariably collapse from the weight of the soil after only a few rains. But we both loved the look with its strong shadow and textural contrast against the green surface as well as surrounding turf. He also liked the difficulty and intimidating view from the tee on this par 3.

Now let me explain how a modern revetted bunker adds contrast from a golf architect’s point of view. See the sketch below. Let’s highlight the three hole locations on this green by using contrast: the left-front, the middle and the back-right. By adding a steeper slope at these locations, they highlight the required golf shot. The problem in the past has been these steeper slopes require additional hand maintenance and increased labor. But if these areas were constructed with artificial turf, it will actually reduce maintenance as no mowing will be required. With sustainability a major theme today, the timing for this artificial turf bunker face seems appropriate.

Conversely, revetted bunkers built with artificial turf is a great solution, but also a great worry by this architect. It is wonderful in small doses but can be overdone. Let’s Look at the Old Course at St. Andrews. Close to 90 percent of the bunker shots played on the Old Course now are sideways or backwards. The golfer who has hit into one of these has no hope. They become water hazards exacting a one-shot penalty. They should be hazards, of course, but where does hazard end and sacrifice on the alter of appearance begin?

Aren’t we supposed to give a golfer hope that he can extract himself from the hazard with the potential to save par?

And let’s talk aesthetics. Do you think bunkers on the Old Course look natural? Of course not. Peter Thomson absolutely hated the bunkers on the Old Course, not so much because of the revetting, but because they are virtually all just cylinders in the ground. Don’t get me wrong. I think the judicious use of revetment is ideal, but if every bunker is revetted, it can provide an unnatural geometric appearance.

While we are on the the Old Course bunkers, it is interesting that many are mostly hidden from view not for any architectural reason but mainly because they developed when the course was played in the other direction. That's why so many players who don't know the course get in them. They can't see them. On the other hand, the latest additions on the Old Course – most obvious at the 2nd where the original bunkers have been moved nearer the green – are obvious and the famous Road Hole bunker itself, which is now a pit compared to the rather shallow affair it was back in Bobby Jones's time, now stares you in the face. Is this good architecture or just making the golf course harder to keep up with tournament play?

The use of artificial revetted bunkers has many advantages, including less maintenance and improved sustainability. But let’s not get too carried by using them on every bunker of the golf course. Used judiciously, they provide interest and artistic contrast. As John Mayer sings in Gravity, “Oh twice as much ain’t twice as good.”

Tim Liddy, ASGCA, founded Tim Liddy/Associates Inc. in 1993. He has collaborated extensively with Pete Dye, designing and renovating some of the most acclaimed golf courses built in the last three decades.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Tartan Talks 116: Doug Smith

- Audubon International adds 127 golf courses to Monarchs in the Rough

- USGA’s GAP preps for fourth year

- Protect your vehicles from rodent damage

- VIDEO: Fun with fairways

- From the publisher’s pen: Humble giving

- Syngenta adds two to western U.S. team

- The Aquatrols Company introduces soil surfactant for Canada