Marion Hollins developed it. Alister MacKenzie designed it. Juli Inkster grew up around it.

Within Pasatiempo Golf Club are carefully restored bumps, barrancas and bunkers. The layers of historical and architectural significance inspire superintendent Justin Mandon each time he passes through the gates of the semi-private club in Santa Cruz, California. Now in his eighth summer at Pasatiempo, Mandon has enthusiastically entered the 100-acre site more than 2,000 times.

“There hasn’t been a day where I have driven through that front gate and seen the Pasatiempo sign that I didn’t want to be here,” he says. “I haven’t lost that.”

It takes an enchanting place to produce extended employee zest. Pasatiempo captivates from the beginning of its story.

When business-minded and golf-talented Marion Hollins needed an architect to design the golf portion of a development overlooking the Monterey Bay, she turned to MacKenzie, a Golden Age giant who was completing Cypress Point Club, a revered private course 50 miles down the Pacific Coast. Hollins announced her plans for the Pasatiempo development on Jan. 12, 1928. She joined Bobby Jones, U.S. Women’s Amateur champion Glenna Collett and British Amateur champion Cyril Tolley for the ceremonial first match 20 months later. MacKenzie became smitten with Pasatiempo and lived along the sixth fairway until his death in 1934. “He must have loved it beyond belief if he decided to live on the sixth hole,” says architect Jim Urbina, who has spent more than 20 years restoring MacKenzie’s work at Pasatiempo.

Hollins will enter the World Golf Hall of Fame in 2021. MacKenzie was enshrined in 2005. Inkster, Class of 2000, grew up along the 14th fairway, worked in the cart barn and snack shack, helped pick the practice range, and learned the game at Pasatiempo. The 14th fairway, coincidentally, features a severe barranca, creating strategic interest and mowing conundrums.

Pride and pedigree drive many decisions at clubs designed during the Golden Age of American golf, a stretch beginning before World War I and ending before World War II filled with characters determined to design and build courses packed with … well … character. At Pasatiempo, pride and pedigree influence nearly every decision.

“Simply put,” Urbina says, “I have restored three MacKenzie courses – The Valley Club of Montecito, Claremont Country Club and Pasatiempo – and I’m about to go to Canada to restore the only Alister MacKenzie course ever built in Canada at the St. Charles Club. If not for the superintendent’s willingness to help the architect restore the genius of MacKenzie, those golf courses have no chance. The superintendent is the key to the preservation of those Golden Age designs.”

Mandon understands the physical and historical terrain. He grew up 20 minutes from Pasatiempo in San Jose and learned the game on the region’s architecturally sound and busy courses. But the opportunity to play Pasatiempo eluded him throughout his childhood. He experienced the course for the first time at 19. “I was completely blown away,” he says. “I had never seen anything like it before.”

The 14th hole, where Inkster grew up and MacKenzie molded strategy into the land, left an indelible impression. Ditto for the 16th, a hole concluding with a severely sloped green featuring nine feet of elevation change. Looking back on it, every hole influenced Mandon’s future. He left the Olympic Club, a frequent major championship site in San Francisco, to begin maintaining MacKenzie in 2013.

His team preserves what Mackenzie intended by integrating modern practices and equipment into a continually evolving agronomic program. Preservation and precision are pillars of the program.

Mandon describes Pasatiempo’s putting surfaces as “old, push-up Poa greens.” An abundance of play – Pasatiempo supports more than 40,000 rounds per year – tests the durability of the Poa annua, resulting in diligent cultural practices such as a monthly deep-tine aeration to produce the high-level conditions expected by golf enthusiasts from Northern California and beyond.

A recent purchase possessing characteristics of a tractor and utility vehicle, the Outcross 9060 from Toro, has aided in the deep-tine process. The combination of 4-wheel steering, 4-wheel traction drive make Outcross 9060 highly maneuverable, stable and extremely turf-friendly for usage on surfaces as valued as MacKenzie-designed greens.

Incorporating recycled water into irrigation practices following the completion of an onsite tertiary treatment plant in late 2017 affected agronomics. The shift protected Pasatiempo’s long-term water future – the club also has access to potable and well water – yet Poa annua is sensitive to the higher salinity in recyled water. Salts accumulate within the thatch and organic matter throughout the summer and turf decline can occur late in the year without proper drainage. Deep-tine aeration is required to improve gas exchange and water infiltration through the profile of the 91-year-old greens.

“Typically, in the past, you would buy a deep-tine aerator and you would buy a specific tractor for the aerator,” Mandon says. “But it was a tractor that wasn’t really big enough to do anything else on the golf course and it wasn’t small enough to do other things. It sat in the barn. When the Outcross came out, I said, ‘Let’s get one here, demo it, put a deep-tine aerator on it and take it across the green.’ If it could go on greens, I knew we could also use it for other applications. It might be a little more expensive than buying the traditional tractor, but because it’s so versatile, I figured it could make sense from an ROI standpoint. Once we took it on the greens and realized it was going to work, it just ended up being a home run for us. It’s easy to use and the crew loves it. I couldn’t imagine not having it now.”

The crew uses the Outcross 9060 monthly, with fairway aeration and topdressing among its other current applications. “There are so many different applications for it,” Mandon says. “We’re just getting started.” How would MacKenzie have reacted to seeing a vehicle weighing more than 5,000 pounds with 59 horsepower contributing to the maintenance of Pasatiempo’s fascinating greens and fairways? “I don’t know what he would think,” Mandon says. “But he probably would have thrown a couple of horses back in the barn and grabbed that Outcross right away.”

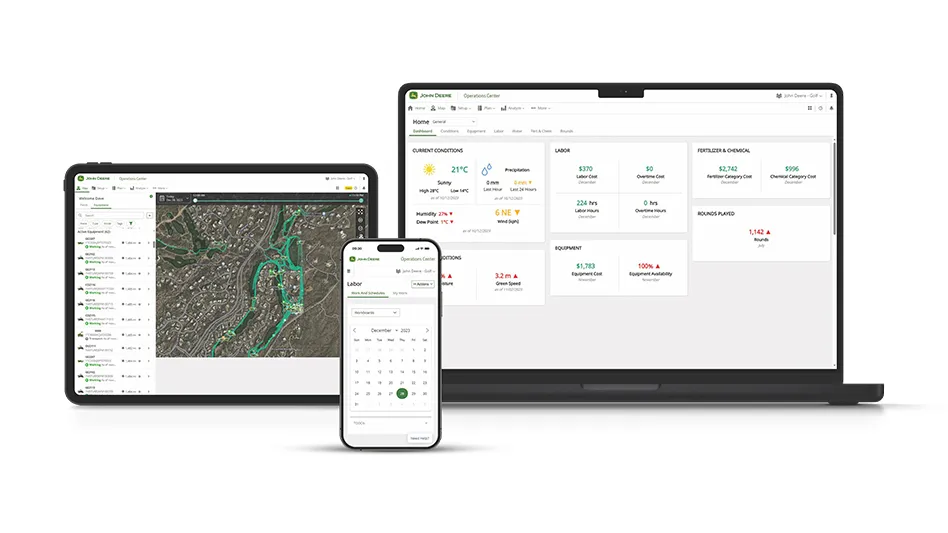

Operator savvy and Toro irrigation technology are also helping Pasatiempo produce pleasant playing conditions and aesthetics. The irrigation system was renovated in 2010 and updated platforms, including the Toro Lynx Central Control System and Lynx Mobile App, have been incorporated into the water management program. Pasatiempo features 66 irrigated acres of Poa annua and overseeded ryegrass surfaces. The Lynx Mobile App allows an operator to control irrigation from a smartphone or tablet and offers instant access to records and hole-specific conditions. A longtime proponent of using a handheld radio to control heads, irrigation technician Bill Keller, a golf industry veteran and former superintendent, has embraced the mobile technology.

“Our irrigation technician downloaded the app on his phone and he can’t stop using it now,” Mandon says. “He’s finding himself to be so much more productive by using (Lynx Mobile App) technology. You have to continue to educate your crew about what technology can do. There’s nothing wrong with the way things have been done before, but you need to try new things because it will help you get more done and make your day easier.”

Water management often determines the golfer experience – and career fate of a superintendent – in a place with damp and dry extremes such as Santa Cruz, California. The magic of MacKenzie wanes without calculated decisions and a reliable irrigation system.

“In this part of this country, where we don’t get rain from May until October, your success is often determined by your irrigation system,” Mandon says. “I tell everybody who comes here that might have worked in another part of the country that your water management is it. Water is scarce, it’s expensive and you’re not getting rain to help you during the season. Every single wet and dry spot on the golf course is a direct reflection of how you are managing the irrigation system. You can’t blame it on the rain. It’s all on you.”

Preserving Pasatiempo is a quest without a defined ending. Mandon and his team, which includes assistant superintendents Phil Kuhlmann and Jack York, squeeze restorative projects between daily maintenance. This past spring, for example, the crew used six weeks without play to peel back grass to reintroduce nuances around fairway bunkers. Work continues on 25 acres of non-irrigated native areas established in 2010, trees are continually being assessed and managed, and mowing lines are frequently studied and altered. Mandon also recently collaborated with Urbina to reduce the number of tee boxes on each hole, reintroducing the Golden Age design mentality of one or two tee boxes on most holes. Urbina uses a six-inch binder of old photos and letters collected by Pasatiempo historian Bob Beck to guide design decisions. Dean Gump, the club’s superintendent from 1981 to 2008, first handed Urbina the binder in the mid-1990s.

Once a superintendent studies the binder, the job description becomes implied. MacKenzie’s intent continues to shape Pasatiempo’s present and future.

“It’s our duty as a golf course superintendent and as a department to continue that, maintain that and preserve that,” Mandon says. “And it drives so much of what we do on the golf course.”

Water is scarce, it’s expensive and you’re not getting rain to help you during the season. Every single wet and dry spot on the golf course is a direct reflection of how you are managing the irrigation system. You can’t blame it on the rain. It’s all on you.”

Explore the July 2020 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find you next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Devising safer landings

- SiteOne adds Durentis to product offerings

- Resilia available for purchase in Hawaii

- What can $1 million do for expanding the industry workforce?

- Captivating short course debuts on Captiva Island

- Wonderful Women of Golf 35: Carol Turner

- The Andersons acquires Reed & Perrine Sales

- Excel Leadership Program awards six new graduates