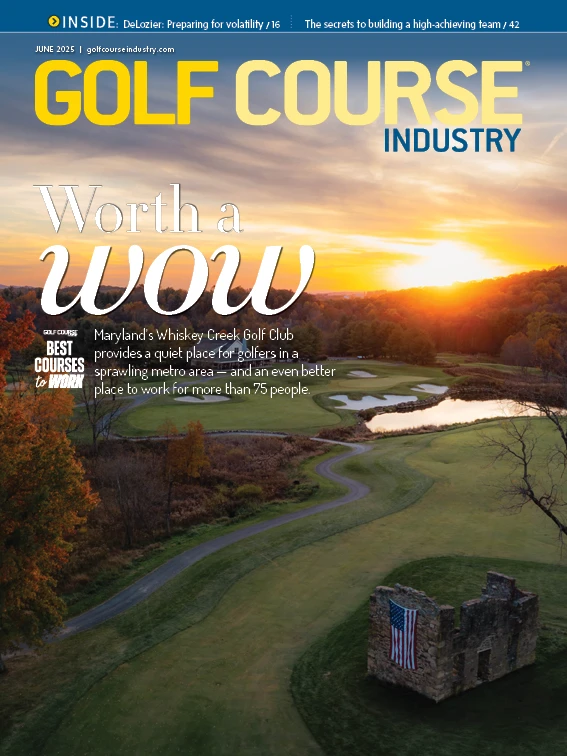

No matter how far you drive to play Whiskey Creek Golf Club — and plenty of people flock to Ijamsville, Maryland, from Washington, D.C., or Baltimore, or other smaller cities an hour or even two out — the anticipation builds the last mile and a half.

Turn in off Fingerboard Road onto Whiskey Road, past a tendril of Bush Creek, past a house or two, farmland in every direction, a thin grass median separating the lucky arrivals from those on their way out. A pair of small traffic circles slows the drive even more. There is no sign of a golf course until the last quarter of a mile, when the 11th hole, a par 3 that dips down into a ravine of rough and back up toward a narrow green, pops into view.

And then, like a mirage in the desert, a parking lot. A clubhouse. An 18th green in front of a panorama of nature.

“The whole idea was to have this curtain of pine trees,” says Ted Goodenow, who started working at Whiskey Creek more than 15 years ago, ran it for years as the general manager, and now oversees it along with three other area courses as a regional manager for KemperSports. “Now, over the years, we’ve gone through two tornadoes, an earthquake, hurricanes — I think the only natural disasters we haven’t had have been a tsunami and a volcano — but the idea was you pull in, there’s this curtain of pine trees, you walk through the gazebo, and it opens up into this” — he gestures toward the panorama — “and you go, ‘Wow.’”

Whiskey Creek is worth a wow. For its Ernie Els and J. Michael Poellot design. For its distant views of both the Blue Ridge and Catoctin mountain ranges. And also for its customer service and its team. Like so many golf courses, Whiskey Creek wants to provide unforgettable experiences. Unlike so many courses, it succeeds because of its people. Late last year, Golf Course Industry partnered with Best Companies Group to create the inaugural list of “Best Courses to Work.” After months of responses, rigorous surveys and more employee Q&As than we care to count, Whiskey Creek emerged victorious.

What separates Whiskey Creek from other courses that participated? The difference starts with Goodenow and runs through every manager to every full-time and seasonal employee.

“Everybody gets trained in customer service,” says Goodenow, whose golf industry career started in 2002 after the courier company he had worked at for a decade went south and he persuaded Mike Carbiener, now the general manager at Sand Valley in Wisconsin, to hire him as the membership director at Holly Hills Country Club in Frederick, Maryland. “I did a lot of cold calling, and I found that if I could go in there and make someone smile — like the guard at the front desk — the barriers come down. Now I can have a conversation.

“And most everyone who’s coming out to play golf, they’re coming out to have a good time. If you can just get ’em laughing and you can start to get them to have fun before they’ve even gotten out on the golf course …”

Goodenow trails off, his attention pulled for a moment by a foursome at the turn, walking into the clubhouse and heading to the bar. He is always thinking about his golfers. He is also always thinking about his team.

He knows he wouldn’t have his job without them.

Goodenow is one of about a dozen full-time employees at Whiskey Creek. The headcount swells to 70 or 80 throughout the summer, from the attendants who drive a cart to your car before you’ve pulled out your bag, to food and beverage folks, to the maintenance team. The customer service training helps Whiskey Creek retain about 80 percent of seasonal employees from one year to the next. So do sensible work schedules, some influence in operations, and general appreciation.

“There’s a big labor force out there looking for work, or looking for a better job,” Goodenow says. “We have to compete.”

Maryland increased its state minimum wage to $15 an hour in January 2024, but neighboring Montgomery County — which borders Washington, D.C., and ranks among the top 20 wealthiest counties in the country by median household income — will implement its annual minimum wage increase next month to $17.65 for employers with 51 or more employees. Whiskey Creek faces competition on all employment fronts.

“Finding good people is really, really hard, and so when you find them, you have to treat them the right way,” says Scott Wisnom, who was hired 16 years ago as director of sales and marketing, is now director of golf, and will likely be the club’s next GM. “The golf business is notorious for long hours and no time away, and I think that’s different here. Ted — and KemperSports in general — really values your time away and that work-life balance. And they tell you that.

“I never, ever want people to feel like they’re overworked. It’s just not fair. Overworked for a week? Sure. Tired for a week? Sure. Tired for four months in a row? It’s just not right, and it’s not what we’re here for. It’s not good for the health of the organization and it’s not good for the health of the individual. We’re not here just to work as long as we can.”

Wisnom has worked as a lifeguard and a camp counselor in his native Pittsburgh. He has also labored for his grandfather’s plumbing shop, often digging ditches, and sold radio ads for a major media company before pivoting to golf. He understands hard work. More than that, he understands treating employees fairly.

“Always ask if there’s a way to do something better,” he says. “What can I do to make your life easier? Do you have all the tools that you need? Do you have all the resources that you need? Is there anything else that we can do to help? What problems do you see out there? What problems do you see in here? Is there a way that we can be better at it?”

Wisnom says every seasonal employee is at least as important to the club’s success as he is. “I’m sitting in my office half the time doing reports,” he says. “The top part of the pyramid could be chopped off tomorrow and this place will run just fine. If we lose the base of the pyramid, we’ll never survive.” Wisnom stresses to every new — and returning — employee that their work is more than a job. “They have a tremendous amount of impact on the guest experience. If we don’t communicate that to them, we’re never going to have that good cycle. It starts with us.”

Longevity matters too. Goodenow has worked for KemperSports for 23 years and at Whiskey Creek for 16. Wisnom has also worked at Whiskey Creek for 16 years. Food and beverage manager Danny Mabry, who turns 41 this month, is just shy of 17 years after moving over from Holly Hills. He has overhauled the menu with the help of chef Devon Gorman — now in his seventh year at the club — and, appropriately enough, has enhanced the whiskey offerings.

Brush Creek was once the escape route for whiskey distilled on the property. According to legend, barrels were rolled over the hillside and floated down the stream before eventually riding the rails to Baltimore. When Mabry started at Whiskey Creek, the drink wasn’t as popular.

“We had some nicer whiskeys,” he says. “But really in the last five years, people have started getting into it. There are a lot of bottles that are hard to find in the market. There’s a lot of allocated stuff that people can’t just go to the liquor store and buy. We’ve had some high-end Pappy Van Winkles, the whole Weller line, the whole E.H. Taylor line. When people come in here, I think our bar gets photographed as much as the golf course.”

A single one-and-a-half-ounce pour of Pappy Van Winkle’s 20 Year Family Reserve goes for $250. Bar manager Sammie Thomas, now in her fifth summer and about to earn her degree in business administration, sold four in a single week last month.

One of the few managers without a long current run at the club is superintendent Drew Matera — though he does have history at Whiskey Creek.

A two-decade-plus industry veteran, Matera worked at Whiskey Creek under grow-in superintendent Bart Miller from 2002 to 2006 — the club’s third through sixth seasons. He built every one of the rock walls sprinkled across the property’s 200 acres and renovated some bunkers that only now need some more work. He left for the top job at a pair of municipal courses in southwest Ohio, then moved back to D.C. for a series of renovation jobs before returning to Whiskey Creek in July 2023. Since then, “We’ve done a lot of tree work and bunker renovations,” he says. “We did stuff everywhere.”

“We trimmed up all the trees on 4 and 8,” says assistant superintendent Brandon Kline, who has worked at the club for 11 years. “We rebuilt a couple bunkers on the back nine.”

“We stripped a bunch of tees that were contaminated with ryegrass, Bermuda, and reseeded ’em, covered ’em,” Matera says, rattling off more recent projects. “They’re not quite there yet. We painted the shop.”

Through every next stop, Matera retained fond memories of Whiskey Creek. “It’s a very mellow, laid-back atmosphere,” he says. “It’s quiet.”

“I’ve had golfers ask me to turn my machine back on,” says J.P. Ross, an irrigation specialist who joined the maintenance team in October 2023. “It’s too quiet when I turn it off.”

“There’s no better setting around here,” Matera says.

Matera isn’t the only Whiskey Creek team member who wandered some before landing in northern Maryland. Head golf professional Mike Jerolamon was born and raised in Clemson, South Carolina, and played guitar for almost a decade in a band called Picture Me Free.

“Toured the country,” he says nonchalantly. “We were opening for Blues Traveler and Marshall Tucker, stuff like that. Some of it was big. Did good, but the band broke up. Went to golf.”

Jerolamon always loved golf. His first memory is throwing a childhood tantrum during a Myrtle Beach vacation because the rest of his family was heading to the pool while he wanted to putt more at the hotel miniature golf course. “My dad stayed with me and let me putt,” he says. After the band ended its run, he shifted to his other passion and tried to make a career. He worked at another nearby course before landing the assistant pro job at Whiskey Creek 10 years ago. He stepped up to head pro less than two years later. And he has no plans to leave.

“It’s just a nice place to work,” he says. “It’s how we treat people. I’ve walked into golf shops at tons of other places and it’s almost like they don’t want you in there. We want golfers to come and have a good time — and we try to make it as fun as possible and not so stuffy.”

Controller Shelly Lang, who joined Whiskey Creek in 2021 after working at Chuck Wade Sod Farm, loves the annual holiday party. The optional white elephant gift exchange is a highlight, but the real fun is the dinner: “Everyone brings a dish,” she says. “We don’t have a signup sheet so it is a surprise as to what will be there to eat. That informal type of planning really represents our staff.”

Add everything together and Whiskey Creek is the kind of place “you want to come to work every day,” says assistant golf pro Steve Shriner, who just started his third season. “There were times I used to dread coming into the office. Not here. It’s a lot of fun. And you get to do a little bit of everything — teach, run the shop, supervise the kids downstairs, just drive around and be outside. There’s never a dull moment. There’s always something going on. You’re always moving.”

Echoing Wisnom’s philosophy about work-life balance, Shriner encourages his summer staffers to chase their career. “If you get an internship in your field and you don’t take it,” he says, “we’re going to have a problem.”

Those seasonal staff members have included both of Goodenow’s sons, now in their 20s, and currently counts Wisnom’s son, a promising high school golfer. Nearly a dozen golf camp attendees have also gone on to work at the club. “And we’ve been here long enough to see them grow up,” Jerolamon says.

Rachel Knapp was never a golf camper, but she has worked four summers in the pro shop. Like Thomas, the bar manager, she’s on the brink of earning her bachelor's degree. She wants to pursue a career as a technical writer. But her years behind the counter have taught her plenty beyond that.

“Growing up, I got my first phone in middle school and I was never social,” she says. “Working here, it kind of just pushes you out of your boundaries. You’ve got to be friendly over the phone, friendly with people who are younger than you, everyone.”

Listen to her on the pro shop phone or checking in golfers for five minutes, and you would never guess she wasn’t already a natural.

“Rachel closes for us while she’s in school,” Wisnom says. “One day, she will not work for us, but she’s been great. She works nights we have leagues and all the guys know her. It’s all about familiarity and making people feel welcome in this environment.

“And if we don’t treat our team the right way, we’re never going to be able to create that kind of feeling when you walk in the door.”

Matt LaWell is Golf Course Industry’s managing editor.

Explore the June 2025 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- From the publisher’s pen: Handicaps and golf management

- Second Sun announces integration with John Deere

- SGL System enters the United States golf market

- 2026 Excellence in Mentorship Awards: Dr. Bruce Martin

- 2026 Excellence in Mentorship Awards: Collier Miller

- AQUA-AID Solutions freshens up

- The Aquatrols Company launches redesigned website

- 2026 Excellence in Mentorship Awards: Justin Sims