Every developer has a little Disney in them.

James Prendamano is probably filled with more of the magic of Walt than most — visions of neighborhoods growing up out of next to nothing, visits to space and, of course, some golf.

Prendamano might not have the seismic entertainment origin Disney created for himself — Prendamano can turn to Google Earth, far easier than Disney famously peering down on Central Florida from a helicopter, picking the plot for his second eponymous theme park — but there are more than a few similarities. Like Disney, Prendamano ventured far from home to build, traveling from Staten Island to Southwest New Mexico. Like Disney, he peered into the future, figuring that an area rich with copper and site of the world’s first commercial spaceport might be a good place to build homes.

And, like Disney, he wants people to have fun.

Prendamano is the owner and CEO of PreReal Investments, long situated in New York, now focused on a remote plot in the Land of Enchantment. Much like Disney wanted to build restaurants and hotels around his eponymous park, Prendamano plans to build more than a thousand homes in Elephant Butte, New Mexico, six miles north of Truth or Consequences and two hours south of Albuquerque, all around Turtleback Mountain Golf & Resort, a gem of a golf course.

“We knew coming out of COVID, people wanted to get back to the outdoors, people wanted to be more in touch with nature and, I don’t want to sound corny but I’m a big believer in this stuff, their inner self,” Prendamano says. “COVID broke the rat race that I lived for 30 years. You don’t know why you’re doing what you’re doing, you don’t know why you’re dealing with quality-of-life issues, you don’t know why you’re sitting in traffic an hour and a half each way. You just kind of fall into it. You get locked in this vacuum and you don’t know what you’re missing.”

So he headed west to what he describes as “kind of like the final frontier.” He and his business partner, Dave Berman, scouted widely and wound up in Elephant Butte. The copper mines there, he figures, will be key to building artificial intelligence data centers, and wealthy adventurers will eventually flock to the region to be launched into orbit from SpacePort America, situated just 25 miles southeast of the city. More than 320 days of sunshine every year doesn’t hurt.

And neither does golf.

REAL ESTATE DEVELOPMENT helped spur the golf course construction boom of the late 1990s and early 2000s, and while it isn’t the driving force behind the current course bump, it remains an important factor. According to National Golf Foundation research, property values of homes on golf courses increased about 15 percent during the first half of this decade.

Turtleback Mountain is at the heart of all those homes Prendamano plans to build.

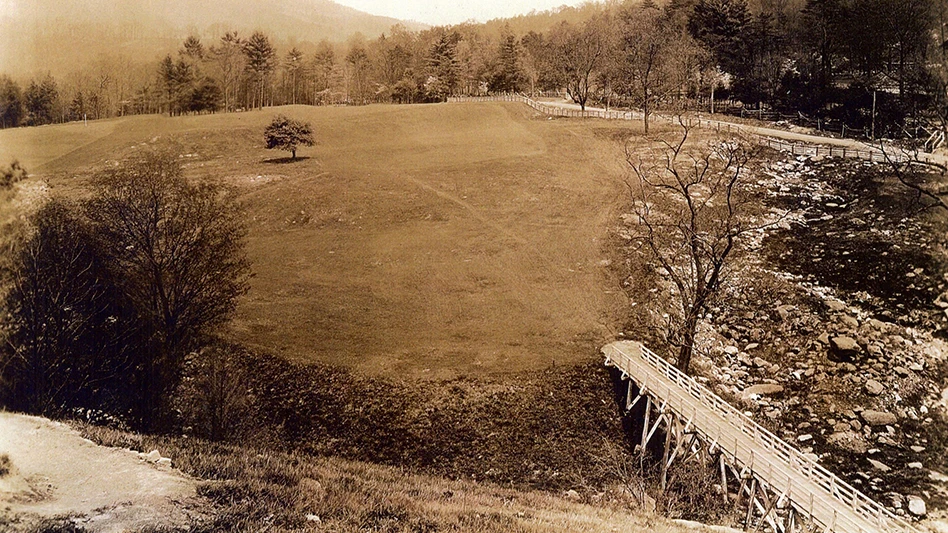

Designed by Dick Phelps and opened in 2007 as Sierra del Rio Golf Club, Turtleback Mountain is a very good course. Prendamano thinks it could be great. But when he purchased it three years ago, it was in shambles. The 70 or so acres of manicured turfgrass were far from green. Many of the nearly 100 bunkers were either filled with standing water or so hard “it was like you were hitting off concrete,” Prendamano says. The driving range sat on top of an old landfill and went six years without water.

Prendamano knew enough about golf course maintenance to know that the fixes were well beyond his skills. He hired Thomas Hams, formerly the superintendent at Torreon Golf Club in Show Low, Arizona, to revive the course.

“When I got here, the big project was getting back to the science and going into the soil,” Hams says. “There were a lot of issues here that needed to be addressed. My first step was just going from the roots up.” Hams pauses for a moment. “My wife said, ‘I don’t know how you’re going to change this around.’ And I said, ‘Trust me. It just needs the love that a golf course needs.’”

Hams dug deep — literally and figuratively — while Prendamano worked with the city, the county and the state engineer. Prendamano purchased the rights to the water beneath the resituated driving range. The maintenance team, meanwhile, worked with golf course architect Rick Phelps — Dick’s son — to rebuild every bunker, lining about two-thirds of them with Better Billy Bunker and seeding the rest to become grass bunkers.

Returning nearly three dozen bunkers to turf didn’t change Ham’s approach to maintenance too much — “It just increased my fertilized area by three or four acres,” he says — though it did change his strategy for fairways.

“Everything was really wide,” Hams says. “It looked like a driving range on the golf course. So, I tightened up the fairways, essentially expanding the rough to give it more of a refined look and showcasing the course layout. I did that on my own. Just kind of walked out the course and was like, Eh, let’s change this here, let’s move this here, let’s bring that out over here, let’s make this dogleg left really hit hard to the left instead of just gradually leaning out. It increased our slope a little bit as I changed the fairways out.”

A superintendent with an architect’s eye?

“We knew we were aligning our goal and our vision with someone who was going to put the mission first and really understood what we were trying to do,” Prendamano says. “It was the right people at the right time. It’s about the people. Without the right people to implement and execute, what do you have? Frustration, and not success.”

Hams has overseeded the course and trucked in hundreds of thousands of square feet of new turf to jolt troublesome spots — most of the course is Kentucky blue rye, with T-1 bentgrass on the greens and Sahara II Bermuda on the driving range. He has swapped out irrigation parts. He has reconstructed tee boxes.

“Improvements over a slow period of time lead to drastic changes,” Hams says. “As long as I’m here, I’m gonna constantly be improving something, clearing out some of the desert just to open up the golf course a little bit more so it doesn’t seem like it’s walled off.” Prendamano calls it “a constant, ongoing evolution.”

Hams jokes that one of the reasons he wants to thin out parts of the course is so he can better spot snakes “if they’re trying to come at me.”

“I’ve just got a mutual respect with them,” he says. “They don’t mess with me, I don’t mess with them. They come at me, then I gotta go at them. I would prefer to not be bit by a snake and have the possibility of dying. That’s my motivation. I want to continue to live.”

“I’ve been in New Mexico for three years,” Prendamano says. “I’ve seen two rattlesnakes and both of them were at a house, not at the course. I haven’t seen a snake yet at the course.”

“Come out a day with me, we’ll see about 20,” Hams tells him.

“Let’s do it,” Prendamano says, his voice rising with excitement. “I go around looking for them. I think it’s the coolest thing in the world.”

“They’re around!” Hams exclaims. He sounds a little like Indiana Jones.

TWO YEARS AFTER opening Disneyland and six years before that helicopter ride, Walt Disney sketched his 1957 Strategy Diagram. Sometimes referred to as Walt’s Flywheel, it maps how every bit of intellectual property — parks, movies, television, merchandise, music, comics, publications — fit together. Prendamano has a similar, if less complicated, approach to Turtleback Mountain.

Last year, the course landed the New Mexico Open through 2027. Rather than just open its gate and welcome all amateurs, professionals and fans, Prendamano let his team run wild. They persuaded 1998 New Mexico Open winner Notah Begay III to return and pulled in two-time PGA Tour winner Matt Every to fly in for the week. Begay, who turned 53 just before tournament week, ultimately missed the cut. Every survived and later discussed his experience on his “Straight Down the Middle-ish” podcast.

“I had a blast playing,” he said. “It was 7,200 yards, but we were at about 5,000 feet elevation, so it was very short and tight, and that was a nightmare for me.

“I honestly hope we do it again next year, because it was a killer time.”

Turtleback Mountain also partnered with KTSM, the NBC affiliate in El Paso, Texas, to stream 24 hours of live event coverage on Facebook Live over four days. The digital strategy generated 3.5 million views and 23 minutes watched per view.

Tournaments bring attention and broadcasts, no matter the platform, bring eyeballs. Prendamano and his team treated a sectional tournament like a major. Will it sell tee times? Will it bring home buyers to Elephant Butte? Will it help send travelers into space?

“You’re only as good as your people,” Prendamano says. “I’ve learned over the years, you surround yourself with people who are a hell of a lot better at things than you are, not the other way around.” He heaps praise on Hams and general manager JC Wright, and his communications and marketing team. “These guys got it,” he says. “They’re cranking.”

Cranking to infinity, perhaps, and beyond.

Matt LaWell is Golf Course Industry’s senior editor.

Explore the February 2026 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- VIDEO: Introducing our February issue

- Solution to a charged situation

- Scott Chaffee joins Advanced Turf Solutions

- Adena returns

- Soil Scout launches Happi100 for North America

- Syngenta introducing microclimate sensor

- From the publisher’s pen: Handicaps and golf management

- Second Sun announces integration with John Deere