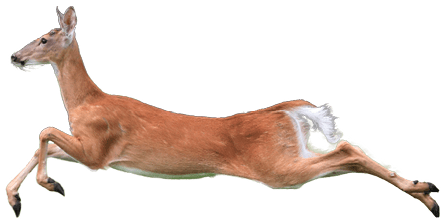

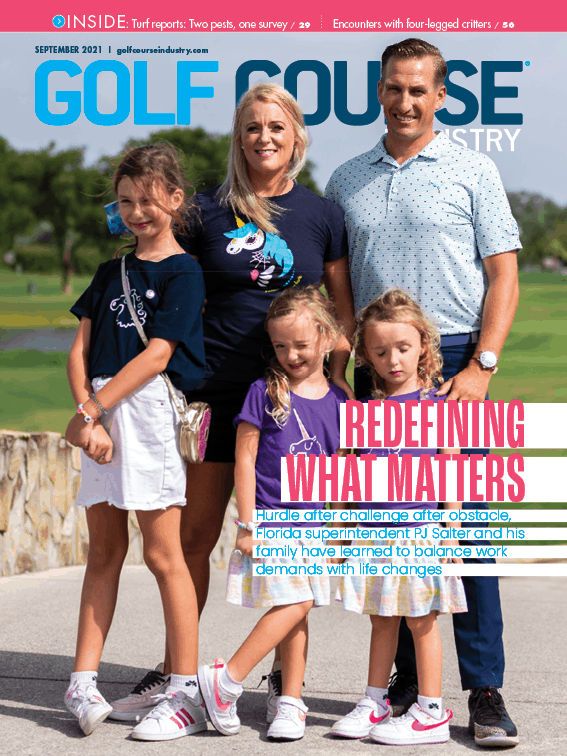

Golf courses are a natural animal attractant. With lush turf enticing animals to search for insects, their plentiful trees, vegetation, and bodies of water prove, well, simply irresistible to a host of different species.

The marauders include skunks, deer, raccoons, beaver, muskrats, armadillos (yep), and, with a nod to “Caddyshack”, groundhogs … and more. Many animals, such as deer and geese, have become very comfortable in suburban settings. They no longer fear people and often will allow golfers to get very close.

Andy Neiswender, director of facilities and operations at Belleair Country Club in Florida, tosses another four-legged pest into the mix: “Since I’ve been at Belleair,” he says, “we have a constant headache from coyotes digging holes in bunkers. The number of coyotes ebbs and flows, and generally when the population is up so is the damage.”

At his previous superintendent’s position at Lake Jovita Golf and Country Club in Dade City, Florida, Neiswender says damage to greens and fairways was done by horses that found their way onto the course and “got spooked” when he approached. “There were places they dug four to six inches into the surface. That ended up costing several thousand dollars in labor to repair and plug the damage.”

When he was at Sundance Golf and Country Club, also in Dade City, Florida, Neiswender encountered “about 10 cows that got out on the course. They walked all over a couple holes and across a green. Fortunately, it was a push-up green with Tifdwarf. It was firm and ended up being more like repairing a couple hundred ball marks.” Also at Sundance, he says, “a sandhill crane got into one of the greens looking for something and ‘roto-tilled’ a 50-square-foot patch of green.”

While the equines, bovines and wandering sandhill crane are rather unusual to find on a golf course, they do point out the damage that animals can do.

At Bull’s Bridge Golf Club in Kent, Connecticut, superintendent Steve Hicks deals with deer making tracks across his greens. “Fixing them is similar to ball mark repair, but more time consuming,” he says. Occasionally, Hicks’s crew must hand topdress with sand to fill the indents.

Turkeys will sometimes scratch up the greens and tees at Bull’s Bridge, leaving a lot of “free fertilizer” to clean up, Hicks says. Coyotes chew on stakes and ropes during the summer. In the winter, they dig at the cups in the greens and “seem to like to use the flagsticks to mark their territory.” Damage from a rather large animal was so bad, Hicks says, that vandalism was suspected on the course’s 12th green. “The flag and cup had been forcefully ripped out of the green. Bear tracks in the bunker nearby clued us in to the real culprit.”

Similar to many courses, no matter where they are, Hicks has also had to fight mole damage. “We had a few winters with no damage, but this past winter, with unfrozen ground and a lot of snow cover late in the winter, one of our greens was badly damaged by tunneling.” It took his crew a couple of days of plugging and topdressing to repair the issue.

Hicks employs preventative measures, mostly for moles, such as mole baits and traps. He also uses coyote decoys near irrigation ponds and utilizes a bird banger cap gun to deter geese from “setting up camp.” The geese, he says, “seem to find an alternative water body as soon as we start to intervene.”

In Maple Grove, Minnesota, Rush Creek Golf Club has a “lot of natural wetland areas” that provide “a perfect place” for muskrats and beavers, superintendent Matt Cavanaugh says. “The muskrats burrow in the soil from the water’s edge and they can go a long way. These burrows create some pretty impressive sinkholes in all areas of the course, including greens. We had a skid-steer fall into said sinkhole. Many of our waterways are connected via culverts and beavers love to plug these up. It has caused some pretty big issues for our drainage and water levels.”

Foxes and coyotes digging in bunkers, all kinds of birds leaving their calling cards on greens, squirrels getting into the outside restrooms and chewing “everything they can get their face on” and animals such as turkey and skunks digging in the rough areas for food (mostly grubs) all keep Cavanaugh up at night.

“If you consider purchasing an insecticide product to control grubs so you don’t lead to turkey and skunk damage, it helps but can get a little costly,” Cavanaugh says. “We have dug channels along some greens, tees and fairways, about 18 feet wide that go down past the water line. We then backfill them with a 2- to 3-inch stone. This makes it very hard for muskrats to dig their burrows in these areas.”

Great Oak Inc. owner Sean McNamara is often contacted by golf courses about problems with geese. “Excessive geese droppings on fairways and greens can be a disgusting problem for groundskeepers and golfers. We are working on a repellent to be named ‘GoosePro’. The problem with most repellents is they don’t work well or last long, or they’re very expensive. We are hoping to develop something that is more effective, works longer and costs less.”

McNamara is also asked often about deer browse damage to ornamental plantings on courses. “Deer often eat arborvitae, rhododendrons, azaleas and other woody ornamental plants during the winter,” he says. “I have seen thousands of dollars in deer browse damage caused in one winter. Spraying winter animal repellent in the fall will protect expensive evergreen trees and shrubs from deer browse.”

Michael Gaunya, president of American Deer Proofing, says that putting up thin 6-foot stakes around greens and threading monofilament, or fishing line, from stake to stake about two feet apart from ground level up, will force deer to steer clear. “They can’t see the line and when the walk into it they get scared and stay away,” he says.

Elliott Dowling, a USGA Green Section Northeast Region agronomist, says courses in urban and suburban-type settings are a natural animal sanctuary in the middle of a town or city. Tree-lined courses or courses with a lot of naturalized rough have more damage because this provides a prime habitat. Dowling has seen “some pretty serious digging” in rough areas, some that required a few pallets of sod or more to repair. “I have not seen, however, the type of damage that courses further south see with wild boars. I’ve seen photos that look really bad.”

Skunks or rodents can best be controlled by eliminating white grubs from turf so that the animals do not have a reason to dig. “There will always be some foraging in areas with a history of white grubs, but as the grub population is reduced, animals will move out,” Dowling says.

Paul Jacobs, a USGA Green Section Central Region agronomist, says the best way to stop animal damage is to be proactive in controlling grubs, especially in rough areas that sometimes get overlooked. “Skunks and even armadillos in the Southwest cause damage by going after the grubs,” he says. Jacobs advises planting shrubs that deer don’t like to eat as a way to minimize damage.

Golf courses and country clubs were among the earliest clients of Brad Lundsteen, owner and operator of Suburban Wildlife Control. “No matter where golf courses are located it is safe to assume all have had conflicts with animals. Because the animals do not understand boundaries and are naturally just doing what wild animals do, the best thing to do is live trap and relocate them.”

Lundsteen “has seen it all” with animal damage on courses. “The worst situations have been raccoons that tore up the grounds so badly that it looked like a rototiller had gone through,” he says. He has also seen beaver dams that have flooded out whole sections of golf courses.

“Another bad scenario I’ve seen, and oddly more than once, is maintenance (crews) mowing the sides of ponds where muskrats caved in the banks and having the mowers fall in or tip over into the pond as the mower passed over unstable areas,” he says. “Luckily, there were no injuries but those could have been very dangerous situations.”

Lundsteen believes that most, if not all “gimmicks” and “animal prevention” devices do not work. “Stuff like mothballs, playing radios loudly, and using coyote or fox urine to try and deter wildlife does not work and is a waste of time and money,” he says. Really, the only good and humane solution is to live trap and relocate the animals as they are discovered, far from the course so they do not return.”

Gaunya says that for superintendents to be effective in preventing or at least minimizing damage from animals, they must remain vigilant. “You need to keep spraying,” he says. “A good rule of thumb is to spray monthly with a quality repellent. If you get heavy rain, you may need to reapply the repellent. If the plants are in a growth stage, you will need to spray more often to get the repellent on new growth that was not there on previous rounds of application.”

Because blasting away at the critters is not a humane option (just look at the results of Carl Spackler’s efforts to eliminate his gopher problem in “Caddyshack”), animal damage is unavoidable to some extent. “We work very hard to create a natural, appealing landscape and I don’t think we are the only ones who appreciate it,” Neiswender says. “The proverbial ‘grass is greener on the other side of the fence’ holds true for golf courses.”

Hicks concurs that animal damage comes with the territory. “Our course is in a serene environment, surrounded by nature,” he says. “We deal with what Mother Nature throws at us, and that includes damage from our wild neighbors.”

A nice sentiment, but there is also no reason to lay down your tools and sprays and surrender your course to animals.

Explore the September 2021 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find you next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Devising safer landings

- SiteOne adds Durentis to product offerings

- Resilia available for purchase in Hawaii

- What can $1 million do for expanding the industry workforce?

- Captivating short course debuts on Captiva Island

- Wonderful Women of Golf 35: Carol Turner

- The Andersons acquires Reed & Perrine Sales

- Excel Leadership Program awards six new graduates