Golf course managers are getting smarter and more comprehensive in their planning. The change is palpable across the industry.

In part that’s due to better training among superintendents. Credit also goes to the professionalization of general managers, who have largely graduated from the ranks of glorified clubhouse overseers to corporate business executives with an understanding of ROI. Golf professionals have also become far more attuned to overall facility performance and the bottom line.

For all that, I still see too many clubs where the planning process is short-term and piecemeal — as if making hash rather than sirloin steak. The signs of it are everywhere as soon as you access the grounds: a classic course, even with a notable design heritage, where in the post-World War II era architects have been shuttled in and out like Elizabeth Taylor’s husbands. Trees planted 50 years ago now overarch the fairways, and even where faint-hearted efforts at “tree management” have taken place they are counteracted by evidence of yet more saplings to fill the newly opened spaces.

There are many courses where a new irrigation system was installed without accompanying plans for infrastructure upgrades or consideration of renovation. The golf landscape is also littered with clubs that have hired an architect to rebuild faulty bunkers in place without due consideration to their possible restoration or movement. Good that they are addressing infrastructure needs. But bad that they isolate the practice from larger planning considerations.

In large measure, the reluctance to think big emanates from a misguided fear that developing a master plan commits a club to master-level spending. Planning big does not require implementing everything; it simply provides a framework for any smaller projects within that larger model. In the process, it eliminates duplicate spending.

Think of it as a deductive process: large-scale planning that establishes small-scale projects. Once you have a master plan in place you can pick and choose projects according to available capital or willingness to tolerate disruption.

Most club members interpret a master plan as a commitment to shut down the course, blow up existing features and present the members with a huge assessment. On the contrary, the cost of a master plan is but a small investment that provides the opportunity to budget, schedule and fix things on a reasonable schedule.

I just got back from an annual meeting of the American Society of Golf Course Architects. Each of these gatherings provides further evidence of the gradual evolution about how architects do their work. Back in the early 1990s, most designers took the approach of being the aloof “auteur” of a process in which their expertise went largely unchallenged by their client and the membership.

That attitude has given way to a far more “relationship-oriented approach” in which the architect makes a long-term commitment. The new approach to a master plan involves working closely with a designated committee whose provenance within the club is not limited to your traditional green or golf committee.

The most successful programs do not hold back from looking at everything comprehensively. That means pool, tennis and pickleball courts, maintenance facility, additional parking, indoor golf performance center, pro shop and cart barn. It also means tending to basic golf course needs as well: trees, irrigation, greens, drainage, bunkers, turfgrass selection, teeing ground equity, cart paths and range.

A master plan is also a good time to consider club governance. A crucial element in club golf operations is how a green committee and chair are populated. The best clubs have low turnover, with “socialization” of service a prerequisite for chairmanship. The worst clubs turn over annually, with guidance equally transitory and the superintendent finding planning impossible since there is no continuity.

And finally, there’s the process of member involvement and approval. Architects today tend to appreciate engagement with members on a limited basis, not sanctioning member input on every detail.

The whole planning process needs to be filtered through a dedicated committee that interacts with the architect and filters knowledge up to the board and out to the membership so there are no surprises. All of which means the members of that committee act as stewards for the club’s welfare, as well as educational guides and advocates.

Clubs that undertake this expanded structure of decision making are likely to have a successful master plan process.

Bradley S. Klein, Ph.D. (political science), former PGA Tour caddie, is a veteran golf journalist, book author (“Discovering Donald Ross,” among others) and golf course consultant. Follow him on X at @BradleySKlein.

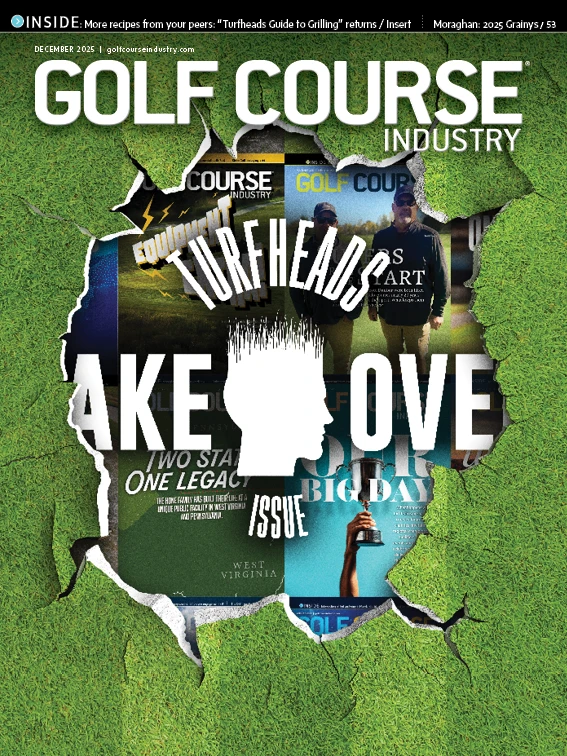

Explore the December 2025 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- The Aquatrols Company launches redesigned website

- 2026 Excellence in Mentorship Awards: Justin Sims

- Foley Company hires Brandon Hoag as sales and support manager

- Advanced Turf Solutions acquires Long Island, NYC distributor

- Twin Dolphin Club earns Audubon International certification

- Carolinas GCSA supports Col. John Morley Centennial Campaign

- GCSAA announces 2025 Dr. James Watson Fellows

- Tartan Talks 115: Chris Wilczynski