Sponsored by

As this year’s State of the Industry report once again shows, the golf industry continues to evolve. As it does, Textron Specialized Vehicles is changing with the times and positioning its brands to serve you better.

2018 continued to be a year of transformation, with E-Z-GO®, Jacobsen®, Cushman® and Textron Fleet Management continuing to deliver new equipment and technologies. We are uniquely positioned to be a single-source solution for a course’s equipment needs, from E-Z-GO golf cars, to Cushman utility and hospitality vehicles, to Jacobsen turf-care equipment and Textron Fleet Management.

In 2018 we debuted our ongoing commitment to innovation with the launch of several new products across our brands and product lines. Jacobsen introduced its TR and AR series, delivering Jacobsen’s unparalleled quality of cut and the ability to tackle hard-to-reach areas of your course. Textron Fleet Management launched its new Shield Plus™ technology, designed for professional turf equipment and utility vehicles. Utilizing geofencing and real-time data, Shield Plus offers a wide range of management features focused on driving efficiency within your operation.

Cushman also added several new vehicles to its line of highly functional utility products. The Hauler 800/800X series, available in either gas or AC electric powertrains, was designed to offer heightened versatility, and can be customized with accessories for almost any job your course demands. And Hauler 4x4 models, offered in gas or diesel, deliver an impressive 2000-lb towing capacity and the power and durability to handle the heavy lifting at your facility.

We are proud to sponsor this year’s State of the Industry report and expect that you will find it informative and helpful as you plan for the future. As the industry changes, you can count on our brands to continue to evolve with it, providing a steady drumbeat of new and improved products and services to help you adapt to change, better serve your customers, and grow a larger, more profitable business.

Sincerely,

Michael R. Parkhurst

Vice President, Golf Textron Specialized Vehicles Inc.

INVESTING IN THE NOW AND LATER

Nufarm is a dependable global partner behind thousands of growing success stories. For more than 100 years we’ve been finding effective ways to fight disease, weeds, and insect pressure by turning world-leading scientific breakthroughs into local solutions.

As golf continues to grow and mother nature hands superintendents some real challenges, Nufarm works tirelessly to assure the performance, safety and simplicity of its golf turf solutions. We invest in a proven portfolio of fungicides, herbicides, insecticides and PGRs that can help maximize time and achieve your maintenance goals.

We offer innovations, including Anuew™ PGR, the industry’s highest-performing late-stage plant growth regulator. We also deliver top dollar spot defense with Traction™ and Pinpoint® – two must-have MOAs for your fungicide rotation, controlling even SDHI-resistant strains.

Nufarm is also focused on the bigger picture, taking steps to make the golf course industry and communities we serve better. We developed the EXCEL Leadership Program in collaboration with GCSAA. EXCEL offers leading-edge development opportunities for future golf course management leaders.

Each year 12 assistant superintendents are chosen from many excellent applicants to assemble three times per year for three years. They learn leadership training in areas such as career, community, and industry stewardship. When we announced the creation of the EXCEL Leadership Program in Fall 2016, we believed it would benefit future leaders. We didn’t envision how quickly the positive impact would be realized through new skills, knowledge, alliances, and even career promotions.

Learn more about the EXCEL Leadership Program or connect with our experts any time at NufarmInsider.com. At the end of the day, Nufarm is always here – ready to help solve the turfgrass challenges you face today and support the success you grow tomorrow. That’s why it’s our pleasure to bring you this year’s State of the Industry.

Kind regards,

Cam Copley

Golf National Accounts Manager

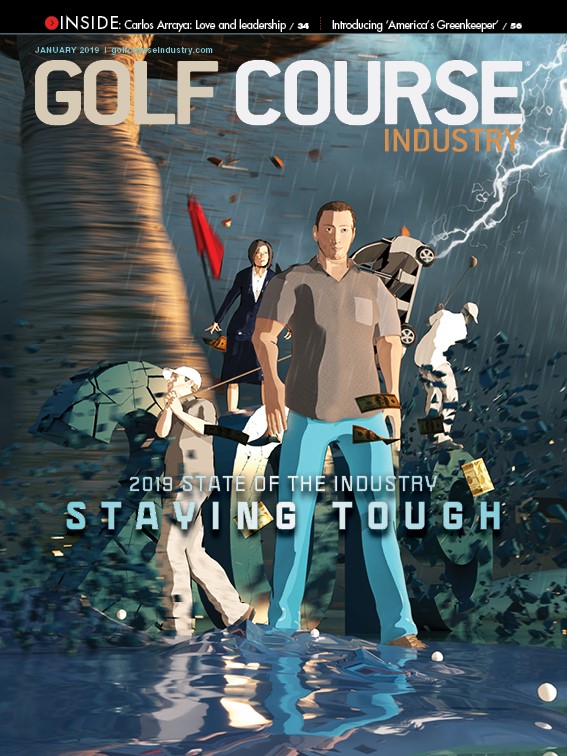

Staying Tough

IT’S OVER

Well, at least the calendar portion of 2018 has ended. With images of saturated and seared turf lingering and labor equations not computing superintendents stagger into a new year with one thought: It can’t get much tougher.

Polled in December as part of Golf Course Industry’s annual State of the Industry survey, 90 percent of superintendents indicated the job is tougher now than when they entered the business. Don’t look for that statistic in any GCSAA or turf school marketing campaign.

From weather swings – What happened to spring and fall in many cool-weather regions? – to shrinking labor pools, managing pristine playgrounds on budgets struggling to keep pace with inflation required athlete grit, actor charisma and artist ingenuity. But conquering enormous challenges such as recovering from a flood, hurricane or wildfire, preserving greens with shallow roots because spring never arrived, and completing the work of 15 with a crew of 10 provides lasting fulfillment.

“It’s hard to say which years are tougher, because you know how revisionist history can be,” says Jim Huntoon, superintendent at Heritage Club in Pawleys Island, S.C. “But as I have done this longer, I have gotten better at dealing with it. You get better at understanding there are things you can’t control, and you just prepare the best you can and figure it out.”

Results of the survey, now in its eighth year, won’t simplify a tough job. But they should prove reassuring and provide snapshots of budgets and attitudes following a year that has thankfully ended.

“I’m optimistic 2019 is going to be a better year, because I can’t imagine we can have a repeat of 2018,” says Robert Alonzi Jr., a second-generation superintendent at Fenway Golf Club in Scarsdale, N.Y.

A couple of details about our methodology. Golf Course Industry administered the survey online via SurveyMonkey. The survey, which was demanding because of the budget detail we asked for, generated 186 responses, with 53 percent of respondents working at private golf courses. As an incentive to complete the survey, Golf Course Industry committed to making a substantial donation to the Wee One Foundation, a charity group started in the memory of Wayne Otto, CGCS, that helps superintendents and other turf professionals in need.

Fenway Golf Club Scarsdale, N.Y.

Coping with comparisons

Choosing to become a superintendent in the New York City metropolitan area means hearing and handling comparisons. The region, after all, boasts dozens of clubs vying for Top 100 recognition.

“Expectations for all courses, from the lowest level to the highest level, run high,” Fenway Golf Club superintendent Robert Alonzi Jr. says. “It’s a concern and it’s something you have to balance.”

For Alonzi, a second-generation superintendent, and his Met GCSA colleagues, meeting expectations developed into a soggy, sultry and stressful task in 2018. Fenway received more than 60 inches of rain, with three-quarters of the total arriving after July 1. Fenway lacks wall-to-wall cart paths, so members needed to follow rigid rules implemented to protect vulnerable turf. “It was hard to live up to member and personal expectations,” Alonzi says.

Challenges extend beyond enormous expectations and weather. Being positioned in a community where the median home price hovers around $1 million nearly eliminates the possibility of attracting workers who reside within 30 minutes of the club. And then there’s an impending budget reality: a mandated $15 per hour minimum wage reaches Westchester County in 2021. “There are certainly a lot of things that I don’t recall worrying so much about when I first became a superintendent or even when my father was a superintendent,” Alonzi says.

Even as colleagues and friends leave the business, Alonzi continues to display zest for the profession. Alonzi expects to begin 2019 fully staffed and the club has commissioned architect Gil Hanse to update a master plan developed in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

“Working in the Met is fantastic,” Alonzi says. “It’s a great area of the country. Some of the greatest courses are within that area. It’s hard to stick out sometimes, because you’re surrounded by such fantastic classic golf courses and country clubs. It’s very competitive, but at the same time, very fulfilling.”

The average non-capital maintenance budget has increased by $223,205 since 2012.

Highland Course at Primland Meadows of Dan, Va.

Beauty and the labor beast

Brian Kearns jinxed himself at the Carolinas GCSA Conference and Show last November, telling colleagues the Highland Course at Primland avoided weather-induced hassles other facilities faced in 2018. “A day later,” he says, “we had the worst ice storm I had ever seen here. So, 2018 can go bye-bye!”

The storm damaged tree limbs along the Highland Course, one of several amenities at a majestic resort in southern Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains, and cleanup continued into December. At least the half-inch of ice arrived at a slow stretch.

With valet parking only at the clubhouse and luxury treehouses along the course, Primland tussles for seasonal business in one of golf’s smallest sectors: the high-end resort market. Kearns has experienced every golf event in the resort’s history, joining the management staff in 2004, two years before British architect Donald Steel completed a course without a par 4 until the fifth hole. Kearns’ duties as superintendent involve attending sales and marketing meetings. Gaining a competitive advantage requires adding amenities maintained by the agronomic team such as a disc golf course and hiking trails.

“When you have a membership, you have that cash flow coming in,” Kearns says. “With a resort, you’re relying on day-to-day business. Our budget has remained pretty level for the last several years. It hasn’t declined, but our responsibilities have increased.”

While visitors hail from across the Northeast and Southeast, a rural location makes finding enough bodies to handle the increased responsibilities a tricky task, especially in a prosperous year. Kearns received an unexpected labor gift when a pair of unemployed corporate supervisors needing work joined the crew at the start of the Great Recession. Those days are gone. In 2018, the crew operated at full capacity for less than two weeks.

“Labor is by far our biggest challenge,” Kearns says. “We probably had the best staff we ever had (in 2018). We just need more of it.”

Conway Farms Golf Club Lake Forest, Ill.

Time for tiers

Multiple students have recently contacted superintendent Connor Healy about pursuing internships at Conway Farms Golf Club.

“Before, if we got one, I felt like I was winning the game,” Healy says. “To potentially have multiple interns is winning the game. I feel very fortunate to be in that position.”

A revitalized internship program is one of several tactics Healy hopes will help Conway Farms combat a dwindling labor pool in Chicago’s private-golf-rich north suburbs. Following a 2018 slowed by either record cold or rainfall in the spring months, Healy reevaluated how he approaches labor.

Instead of relying on traditional tenured-based tactics, he’s implementing a performance-based compensation system for workers. Hourly dollar amounts are attached to six tiers of employees and motivated workers can advance a tier as early as three to four weeks after joining the crew. The system is designed to keep the labor budget manageable while dangling the recruiting hook of early advancement. Healy also views the changes as a proactive measure for what he considers the “inevitable” escalation of the region’s minimum wage to $15 per hour.

“A lot of things seem to be coming to a head all at the same point, it feels like for me,” he says. “There’s this dramatic labor pressure out there, there’s wage pressure and there’s also low unemployment. There just aren’t enough people to fill the jobs from the pure labor perspective, but also from the higher skillset, there aren’t as many people out there who want to become assistants. Positively, I’m starting to see a little more from my efforts as far as people getting back to me about wanting to work (in 2019).”

Healy’s crew should be backed by significant resources. The Tom Fazio-designed course, which opened in 1991 and hosted the PGA Tour’s BMW Championship in 2013, 2015 and 2017, is continually examining the condition of its infrastructure. “I feel fortunate to be at a club that’s committed to investing,” Healy says. “I see it pretty readily throughout the area.”

Otter Creek Golf Course Columbus, Ind.

Tough beginnings

Brent Downs didn’t receive much of an opportunity to settle into his new job as superintendent at Otter Creek Golf Course, a public facility in the Transition Zone city of Columbus, Ind. Downs arrived in March. From May 7 until June 28, the course absorbed 20 inches of rain.

“I would describe it as the most difficult year of my career,” Downs says. “Different regions of Indiana got different amounts of rain, but Columbus seemed to be in a rain corridor. On the days it didn’t rain, we were over 90 degrees and overnight temperatures were in the mid-70s. That made it a really difficult environment to grow grass in.”

Otter Creek, a 27-hole facility that debuted its first 18 holes in mid-1960s as a gift from the Cummins Engine Co. to the city of Columbus, supports a variety of golfers, ranging from scratch players competing for state titles to beginners. Unfortunately, there were times in 2018 when nobody played the course. Otter Creek lost an equivalent of 15 full-play days from Memorial Day to Labor Day, according to Downs. Riders account for most of Otter Creek’s play and cart path only rules negatively affect business.

The course possesses six holes within a floodplain. The 11th hole lost a significant portion of its bentgrass/Poa annua fairway because of weather-related damage last season. Through the muck came one of Downs’ proudest moments, as his team needed just two months to reseed and revive the surface. “That took a lot of people, a lot of hard work and a lot of resources,” he says. “In a way, my biggest embarrassment, became our greatest accomplishment.”

Connecting with a loyal crew and frequent communication with his bosses, including using drone imagery to document the damage and recovery, helped Downs endure a brutal year.

“Nobody wishes for a year like this to happen,” he says. “But I’m glad it happened in my first year, because I kind of saw the course and all the drainage challenges it presents up front, so now we can get to work fixing them.”

Heritage Club Pawleys Island, S.C.

Avoiding disaster

Jim Huntoon contemplates aloud 15 minutes into an interview about his 2018 experiences maintaining a golf course in the crowded Myrtle Beach, S.C., market.

“We haven’t even talked about hurricanes,” he says.

After getting walloped by Hurricane Matthew in 2017, Heritage Club, where Huntoon has spent nine years as superintendent, dodged the crippling parts of Hurricane Florence. But that didn’t make 2018 a soothing year.

Snow and below-freezing temperatures closed the course for 10 days in January, unseasonably cool temperatures in March and April hampered spring business, and flooding of the Waccamaw River following Hurricane Florence created uneasiness in September. Seeing his crew and the club’s other departments work in harmony to prepare for a worst-case scenario that didn’t arrive following Florence enthused Huntoon.

“I’m happy we don’t have any natural disasters to pick up after,” he says. “We are getting a lot of stuff done this winter. I try to keep a positive outlook. This thing can beat you down so fast. If I didn’t truly love it, I wouldn’t do it.”

A two-decade veteran of the Grand Strand, Huntoon observed how changes in the region’s golf market are benefitting Heritage Club. Instead of relying on tourists to carry revenue burdens, steady year-round play allows quality facilities to recover from a disappointing March and April. Even in a cranky weather year like 2018, Heritage Club supported 60,000 rounds. Huntoon has adapted his agronomics to fit an evolving business model, bypassing overseeding bermudagrass surfaces and maintaining reasonable speeds on severely contoured greens.

“Myrtle Beach has changed a lot over the last 15 years,” he says. “It used to be that the spring and the fall were everything to business, catering to the package player and tourists. But so many people have moved down here, so wintertime has become more important and certainly summertime has really changed a lot because there’s a lot more business.”

Minot Country Club Minot, N.D.

All alone

Minot Country Club has one constant on its turf team: superintendent Chris Strange. In fact, he’s the North Dakota club’s only full-time agronomic employee.

Destroyed by a flood in 2011, the club unveiled a new course on a different site in 2015. Strange, who arrived in Minot, a North Dakota city on the periphery of the energy-rich Bakken Formation in 2013, worked alongside several different assistants until losing one to an Arizona club in 2017. The position remains vacant.

“We didn’t have a good candidate pool,” Strange says. “That was different from 2013 when we were building the course. When I had that job posted, the rest of the United States was going through a recession. We had a lot of applicants then and people were flocking to North Dakota for jobs. It was a different ballgame than last year.”

Minot CC’s labor situation might be as unforgiving as a hardened landscape where winter temperatures plummet to minus-40 degrees and summer readings soar past 100. Entry-level energy jobs advertise starting wages of $20 per hour and more. Strange prepared to spend another work winter alone as he awaits the annual spring arrival of workers obtained via the H-2B visa program. “They’re my only solution every year,” he says. “I’m always on pins and needles waiting to see if we get our visas.”

Golf is a seasonal game in Minot, with Strange working almost daily from mid-April until the end of the October before receiving a winter respite. Turf stress following a dry 2017 tested Strange in the early parts of the 2018 golf season. Once the crew arrived and conditions stabilized, the course continued to mature, allowing the club to satisfy a young membership that plays the bulk of its golf on weekday evenings. The recent drilling of a second irrigation well should help the club handle wild weather swings. “We will have a reliable water supply in 2019,” Strange says, “and that will be a game-changer.”

Haggin Oaks Sacramento, Calif.

California creativity

It takes more than an accessible and affordable course designed by a Golden Age juggernaut to make a municipal facility bustle these days.

Consider Haggin Oaks, a 36-hole City of Sacramento facility operated by Morton Golf Management. Alister MacKenzie designed one of the two courses, yet modern revenue-generating tactics include a golf expo, “Golf and Guitars” country music festival, FootGolf, and hosting major cross-country races.

“There’s a lot of stuff going on that they don’t teach you in turf school,” says Morton Golf director of agronomy Stacy Baker, who oversees the maintenance of the MacKenzie Course and Arcade Creek at Haggin Oaks. “You have to put your other hat on and think about it as a business and not just 18 greens.”

Baker leads a crew ranging from 18 to 22 workers during the peak summer season. Pulling workers away from agronomic tasks to help with event setup is a common – and accepted – practice. Haggin Oaks supplements its crew with volunteer labor, a sign of the facility’s value as a community asset.

The golf statistics are jarring: Haggin Oaks occupies 593 acres and its 42 greens cover more than 300,000 square feet. The two courses receive a combined 70,000 to 100,000 annual rounds depending on the weather and offering starting wages of $14 per hour yields few job candidates. Operating a crew of 18 in 2018 cost the same as a 24-person crew a few years ago because of California’s rapidly escalating wages, Baker says. To handle the increased workload, Baker has developed a versatile team.

“We don’t have titles here,” he says. “We don’t have an irrigation tech, we don’t have a spray tech, we don’t have three assistants. Besides myself and my equipment technician, nobody has a title. We all pitch in and we all can do most of the jobs.”

As the scope of Haggin Oaks evolves, the weather also changes. Smoke from the Northern California wildfires of 2018 reached the course, forcing employees to wear dust masks for multiple days. Despite the formal end of the most recent California drought, water remains a concern. “Whether it’s a drought, whether it’s El Niño, whether it’s smoke from fires … it just seems like every year you need to be prepared for some sort of weather event,” Baker says.

Explore the January 2019 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Audubon International announces newest leadership appointees

- Southern golf trifecta

- Sports for Nature Framework gains new signatories

- Camiral Golf & Wellness upgrades Stadium Course

- Troon selected to manage The University Club of Milwaukee

- Kafka Granite adds new business development manager

- GCSAA celebrates 10-year anniversary of collaboration with Congress

- DLF launches new seed enhancement solution