The oldest golf course in Palm Springs isn’t swinging a narrative merely historic and halcyon. Rather, the O’Donnell Golf Club — which debuted in 1926 and has played its current 9-hole course since 1929 — is proving among the more proactive tracks across the Southern California desert’s 120-course bounty.

And the private club is doing as much as the only Coachella Valley course irrigated with domestic water.

About five years back, amid extreme California drought conditions, O’Donnell received a faucet wake-up call from its water provider, the Desert Water Agency, a not-for-profit agency and state water contractor that provides water to approximately 24,000 domestic water connections, serving about 75,000 people.

“DWA came to us and said, ‘If you guys continue to use water the way you’re using water, you’ll have to demonstrate to us why we should let you overseed and water,’” says John Essell, co-chairman of the club’s greens committee. “That’s when the flare went into the sky.”

That flare received subsequent flame at the region’s now infamously candid and alarming Coachella Valley Golf and Water Summit, held at the onset of 2023. Among the gathering’s nearly 175 attendees were Essell and nationally renowned turfgrass scientist Dr. James Baird of nearby University of California, Riverside.

After the two men were introduced, Essell compelled Baird to visit the 33-acre O’Donnell grounds for the first time. The sojourn prompted, as Essell recalls, Baird’s response of, “Well, now I know why I’m here — you guys are using way too much water.”

O’Donnell’s agronomy mind-meld plays as unique as the serenity of its historic setting. Tucked adjacent to the San Jacinto Mountains and a mere block from the downtown Palm Springs’ main strip din of drink, dine and tourism, the grounds’ enchanted presence sits unknown to most desert vacationers.

The club’s nine holes are played in wraparound as a 5,310-yard card with staggered tees. The time-honored course and buildings were recognized by the National Register of Historic Places in 2020.

Working with a third party for its course maintenance, former and present course brass has leaned on the passion of Essell, the métier of Baird and the trusted hand of longtime and now-retired desert superintendent Roger Compton as turf consultant. In a bit of irony, Compton’s storied, full-time Coachella Valley career concluded at Thunderbird Country Club, the Coachella Valley’s oldest 18-hole course.

For a team motivated by cost and sustainability alternatives and initiatives, irrigating with domestic water does not a hot drop make.

“We’re on a meter here, measuring by cubic feet,” Compton says. “My whole life [previous to working with O’Donnell], we’ve measured by acre feet. But we’re in the ballpark of where we should be for usage. The problem with the water here is that it’s about $1,000 per acre-foot; as opposed to other places here in the mid-Valley, which pay closer to around $280 per acre-foot, and much less than that in the east Valley. So, it’s tough — and we’re definitely not wasting water with what we’re paying.”

Alternate water source options prove unfeasible.

“We’ve twice had somebody out here just to eyeball whether we could put a well out here, how far from the mountain,” Essell says. “And the general consensus — based on the mountain proximity, because the granite is so thick — is that’s there just no way to drill into it. And then the other part is seeing if we can get the reclaimed water, the closest of which is 2.3 miles from here. So, that’s not gonna happen. We’ve got to live with what we’ve got.”

Searching for solutions and savings, O’Donnell has opted for a card equal parts reinvestment and experimentation. Add a dash of spirited youth, and the nearly 100-year-old course is driving toward the future as much as acknowledging its past.

At the close of 2024, O’Donnell brought on 33-year-old Alexandra Phillips, PGA, as general manager. A former touring professional and long drive competitor, Phillips didn’t take the gig to oversee a status quo.

“Yes, we are the oldest course, but we want to be forward-thinking, we want to help the Valley get into the future,” she says. “And that’s a big part of our water conservancy efforts. We don’t just want to be part of the desert’s history, but to be part of the future.”

The assembled team and motivated frontwoman have made for a unique foursome.

“Roger has been a great consultant, and Mr. Essell has been amazing with the greens committee. They’ve been instrumental in teaching me,” Phillips adds. “Yeah, I learned the basics through the PGA and working at another course and being in golf forever, but it’s a different world when you’re in charge.”

That world has been as much think tank as golf grounds across the past two years.

Adding its name to the desert’s growing roster of an en vogue shift toward eschewing a putt portion of annual overseed, O’Donnell renovated its greens to MiniVerde in 2023.

Pleased with performance of the hybrid Bermudagrass and reputed speed (Stimping at 11.5 in-season), the surfaces have been double-cut and rolled thrice weekly in-season, while adding Primo to slow growth. “There’s a learning curve to it, a lot more work to it,” Compton says of MiniVerde.

Along with the new greens (coupled with a 1,500-square-foot MiniVerde sod farm), the club’s further conservation efforts have included: allowing rough to go dormant in winter; namely turning heads off (approximately 60) in non-overseeded rough; a full rebuild of the pump house’s injection system; and, a summer 2025 project replacing nearly 180 heads/internals.

Now regularly irrigating just 11 of the grounds’ 33 acres, O’Donnell is assessing course performance with the satisfaction of its avid 235 golf members.

“There are challenges, with water being our biggest,” Phillips says. “Not only the state’s drought issues and trying not to overstay our welcome in the regard, but also, of course, the cost. We have a small membership, and we want people to enjoy their time here. The upcoming irrigation project is going to be huge for us, being able to save almost 14 acres of watering over the winter.”

While such efforts and aims may prove par for the course, other club initiatives are more mad turf science.

After Baird started sampling the effects of surfactants and wetting agents, the good doctor followed the Hoganism of finding secrets in the dirt.

On the club’s eighth tee box, a Baird-led project planted four drought-tolerant Bermudagrass hybrid grasses for study. The test plot monikers include: Latitude, Tahoma, TifTuf and the locally homaged Coachella.

Additionally, adjacent to the No. 2 tee box on the property’s polar end, a near-1,800-square-foot plot is also testing quad of drought-tolerants, matching Tahoma and Coachella with TifTuf and Bandera.

“We put up these signs here so that the members could see what we’re doing,” Essell says. “And, working with the guidance of Dr. Baird and his graduate team, we did this project and left it basically dormant, irrigating about once or maybe twice a week. We did nothing else — except a very occasional mow — and just watched how they transitioned.”

Balancing reality and hope, while Compton would no doubt celebrate a wall-to-wall drought-tolerant overhaul, the veteran grassman is seeing an eventual fairway and green surrounds resod as more likely.

Standing by the ninth tee box, Compton says: “I would love hybrid Bermuda tees. But in order to do that — and let’s say we wanna widen this tee — when you regrass it, and let’s say you only regrass the tee-top and replace it with a hybrid and leave the other Bermuda, in three or four years with a few feet here and there, you’re right back to Bermuda. You can work on it, but you can’t keep it out.”

Baby steps to continued conservation seem more likely.

“Part of this is just trying to understand how much or how little water is needed,” Essell adds. “So, now that we’re almost in transition [in late May], the next part of the process that Roger and I have talked about is maybe taking an area, say, 50 yards in front of a green, putting in one of these turfs, letting it go dormant and seeing what happens.”

With aims both bold and sanguine to eventually reduce water usage by upwards of 20 percent, O’Donnell’s storied past and aggressive present is being met with both hope and back slaps.

“We hosted our own water summit here, and a few of the gentleman, along with the rep from the Desert Water Agency told us that they thought what we were doing was setting the chart for other courses in our Valley,” Essell says. “They all expressed, regardless of water source, how important it is to recognize the value of these resources, along with the steps that need to be taken to conserve. They told us we were at the forefront of this effort.”

Judd Spicer is a Palm Desert, California-based writer and senior Golf Course Industry contributor.

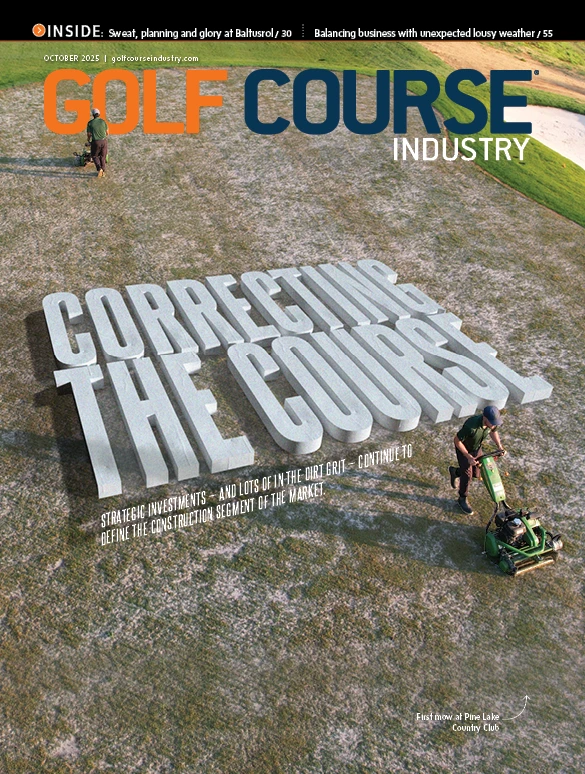

Explore the October 2025 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- The Aquatrols Company launches redesigned website

- 2026 Excellence in Mentorship Awards: Justin Sims

- Foley Company hires Brandon Hoag as sales and support manager

- Advanced Turf Solutions acquires Long Island, NYC distributor

- Twin Dolphin Club earns Audubon International certification

- Carolinas GCSA supports Col. John Morley Centennial Campaign

- GCSAA announces 2025 Dr. James Watson Fellows

- Tartan Talks 115: Chris Wilczynski