There’s a silent assault on the most scrutinized parts of golf courses. The effects of aggressive soft spikes on greens is an increasingly common sight, raising tricky agronomic and sensitive political questions and evoking memories of metal spike clanks produced years ago.

There’s a silent assault on the most scrutinized parts of golf courses. The effects of aggressive soft spikes on greens is an increasingly common sight, raising tricky agronomic and sensitive political questions and evoking memories of metal spike clanks produced years ago.

New spike models initially snuck up on many superintendents. Something as simple as messages from the pro shop like the ones Curt Brisco receives can make superintendents think a match-ready Lionel Messi had stepped on the property.

“The pro relayed to me on one of these occasions he thought somebody with soccer spikes had been out there,” says Brisco, the superintendent at Fox Prairie Golf Course and Forest Park Golf Course in Noblesville, Ind. “We went out and looked and for a period of time that’s what we thought. Then we were out a couple of weeks later and we had someone out again and found out it wasn’t soccer cleats. It was just this aggressive shoe.”

The Adidas Adizero Tour released in 2013 is the first model superintendents mention when describing the silent assault on greens. The large indentations created by the Adizero Tour led to multiple United Kingdom greenkeepers convincing their respective clubs to ban the shoes. Adidas released the Adizero One, a lighter model the company promotes as being more “green friendly” last year.

Multiple superintendents interviewed by GCI responded they started noticing changes in their greens in the last “two or three years.” Likewise, images from the 2015 PGA Merchandise Show are alarming superintendents because manufacturers are continuing to release shoes with aggressive characteristics, such as thick, unyielding, elongated raised spikes and points of contact throughout sole. Three major golf shoe manufacturers didn’t respond to a GCI request for information about their agronomic considerations when designing new products.

“I have been in golf maintenance for 25 years. I have been in the business long enough to remember when metal spikes were the norm,” says Kevin Breen, the superintendent at La Rinconada Country Club in Los Gatos, Calif. “What a huge improvement it was seeing the quality of putting surfaces when those spikes went away and we went to soft spikes. Lately, with some of the aggressive shoes, I have seen putting green quality decline.”

Breen and his crew maintain small bentgrass/Poa annua greens with high-traffic areas susceptible to aggressive spike damage. The most vulnerable turf surrounds the cup, which is where golfers take the most steps and leave abundant footprints. The damage, He says, is noticeable early in the morning and late in the day when sunlight levels are low. “What I have seen are footprints where I can identify every spike on the bottom of the shoe,” Breen says. “That’s different than what I would have seen with shoes four to five years ago.”

Getting a grip

Blair Rennie begins his 11th year as greens superintendent at Whitevale Golf Club in Whitevale, Ontario, on April 1, and last year proved to be one of his most challenging years since entering the business. A harsh winter forced Whitevale to overseed its 18 regular greens and begin the 2014 season with temporary greens. Rennie started noticing damage caused by aggressive spikes prior to last season, increasing his anxiety about what might happen when the overseeded greens were ready for play.

Rennie discussed the situation with Whitevale’s golf professional, general manager and board of directors. The group reached a consensus to highly discourage members from wearing ultra-aggressive spikes last season. The club hosted events with shoe manufacturers and offered members an opportunity to purchase less-aggressive models at cost.

|

Pro’s perspective Douglas Frazier sells golf shoes and works closely with the person at his course responsible for repairing damage caused by aggressive spikes. He’s also a veteran of industry dilemmas caused by aggressive spikes. Frazier, the PGA Professional at Newark (Del.) Country Club, pushed for colleagues to ban metal spikes at their facilities and he says the soft spike era has now yielded unintended consequences. “Like many well-meaning things in life, it has gone maybe too far the other way,” Frazier says. Frazier, who once worked for a golf shoe manufacturer, says soft spikes are becoming aggressively long. In his view, the situation mirrors the one created by longer metal spikes in the 1990s. “I started noticing it two years ago,” Frazier says. “A lot of it has to do with the platform of the shoe. The spike now sits on a POD. We are a course built in 1921 in the Northeast with push-up greens. I won’t say we are overwatered. But when we are soft, there are indentations in the greens that literally can stay there for two days and mowing doesn’t take it out. I took pictures of spike imprints last summer and actually went to my superintendent to talk to him about whether we should look at doing something.” Newark hasn’t banned any new models of shoes – yet. “I’m at the point of thinking about banning certain types of soft spikes and/or shoes at our club,” Frazier says. Frazier has stopped selling several new models in the pro shop. He says the problems are extending beyond one manufacturer. He ordered eight models of shoes from one manufacturer and the shoes he’s receiving include three different types of spikes. He says the manufacturer isn’t permitting him to order the spikes he wants for the shoes he’s receiving. He has mentioned the turf damage caused by shoes with aggressive spikes multiple times to a sales representative from a major manufacturer. “He seemed surprised that it seemed to be an issue,” Frazier says. Frazier attended this year’s PGA Merchandise Show in Orlando and he played multiple private courses while in Florida. Scenes from the trip are convincing him that challenges caused by aggressive spikes are not confined to one geographic region. “I played at some really nice clubs and there were footprints and an unreasonable ability to make three-footers because of foot traffic,” he says. “It was middle of the day on really fast greens and very sandy greens with not a lot of thatch. They just didn’t have a good root structure, not that anything was wrong with the greens. When you walk up on the first green, you’re like, ‘Wow, these greens are beautiful, but it looks like a pinball machine.’ I don’t know if it’s crisis mode, but that’s where we are at.” |

Whitevale entered 2014 with a plan regarding shoes and turf damage because of what Rennie noticed the previous season. “My brain is telling me that shoe manufacturers are pushing certain brands and certain models on the golfers and trying to sell a product and certain golfers are assuming that, ‘Hey, I need that traction on the golf course,’” he says. “I’m not going to pretend to know all the different spikes, but some of them come to mind. When you see guys walking on the cart paths and you can see light underneath their feet because spikes are holding them up that far off the asphalt, then that makes me nervous.”

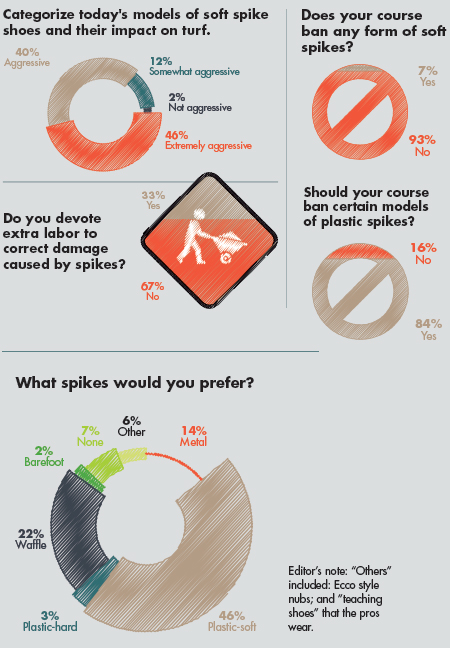

The nerves aren’t confined to one geographic region or turfgrass variety. GCI surveyed 242 superintendents and golf industry professionals about the impact today’s golf shoes have on turf. Nearly half (47) percent of respondents characterized today’s models of golf shoes as “extremely aggressive,” with another 39 percent labeling the shoes as aggressive.

“They seem to have a thicker spike, so it actually makes a depression,” says Cory Brown, the superintendent at Overlake Country Club in Medina, Wash. “They are a lot stiffer. They don’t have that flexibility. I remember when the Black Widow spike came out. I thought that was ridiculous. How can you put this on your greens? But they never really seemed to be much of a problem. The new ones are thicker and they are just stiffer. They don’t have that spread to them that some of the older models had.”

Only 2 percent of respondents classified the new models they are seeing on their courses as “not aggressive.” Rogers Park Golf Course superintendent Bill Kistler hasn’t observed turf damaged caused by new models of shoes on his course. Rogers Park is a public course in Tampa, Fla., with Bermudagrass greens, and Kistler says he’s spotting customers with athletic-looking golf shoes. “You have a lot of different cross sections of players here,” Kistler adds. “At this particular course, we happen to have quite a few low-handicap players out here and I notice a lot of the guys have gone to those multi-purpose shoes, which is what I call them, and it seems to be going over well.”

Melvin Waldron, the superintendent at Horton Smith Golf Course in Springfield, Mo., hasn’t noticed problems on his course because regular players aren’t frequently buying new shoes. Waldron, though, is aware problems exist because of pictures superintendents are posting on social media.

“I’m pretty surprised at what they are seeing,” Waldron says. “Part of me says I would think the shoe manufacturers would do more research with their products before letting them out on the market and then some of it is I wonder, and I probably think too much sometimes: Are we creating part of that problem too because we are mowing so low these days? Part of it also could be green construction. Is it old soil greens and not sand and things like that. That’s kind of what I think when I do see those pictures. It’s hard to say, especially when we don’t see the issue at our golf course, but I think there are reasons for that. We mow at .156. We will stay on a little bit of the dry side because we can with the height of cut, but mostly it’s because we have senior golfers who aren’t buying new shoes.”

Still, Waldron is concerned the problems colleagues are experiencing could spread to his course. “Our golfers are going to have to buy new shoes sometime down the road and hopefully they aren’t buying these types of shoes that have these kinds of spikes and cause these types of issues,” he says. “I’m hoping that with better communication somebody will do some research and we can avoid this issue all together.”

Delete the cleat

Endorsing and enforcing bans can be a challenge, especially at private facilities. Only 7 percent of respondents say their course has banned some forms of soft spikes, but 84 percent indicated their course should ban certain models of spikes. “It’s a delicate issue,” says Scott Schurman, a second-generation superintendent who works at Kearney Country Club in Kearney, Neb. “We don’t try to rub it the wrong way up in the pro shop. We have a good working relationship. If I’m in league play or playing a casual round of golf, I will take note of it. I learned from my dad to tread lightly. Just try to be politically correct about it.”

Kearney Country Club features firm bentgrass greens, and they can be mowed and maintained below one-eighth-of-an-inch when the weather cooperates. A low height of cut might magnify problems caused by aggressive spikes, according to Schurman. “I remember as a kid, and even at times past that, they were mowing greens on the Tour at a quarter-of-an-inch,” he says. “Now we are well below an eighth. There’s not much of a plant there. It’s not like walking on concrete. Height of cut might be part of it, but I’m only finding issues with one brand of shoe. If it was all the other brands, we would have footprints everywhere.”

Member/customer demands for slick greens makes raising the height of cut unrealistic at many private facilities. Superintendents are defending their greens through agronomic practices such as topdressing and frequent rolling to promote firmness. But few defenses exist against spike damage in soggy conditions.

“When there’s more moisture in the soil, we see more damage, no question,” Rennie says. “When we are getting to what I call the shoulder season, early spring, late fall, when the growth of the turf is diminishing and slowing up, it can’t heal from that sort of damage. Once you get into the warm of summer and you can dry things out, you are getting good growth. When we are doing our regular mowing and rolling, I would tell you that it’s not as big of a concern at that time of year.”

Courses with small greens in soggy geographic regions are facing the biggest challenges. Whitevale falls into this category. Rennie says he would like to see golf courses experiencing turf damage caused by aggressive spikes to receive USGA support through research. The USGA Green Section Record published an extensive study in 1983 about the effects of multiple shoe models on putting green quality. The USGA also performed a study on the effects of golf-sole shoes on putting greens in 1958-59.

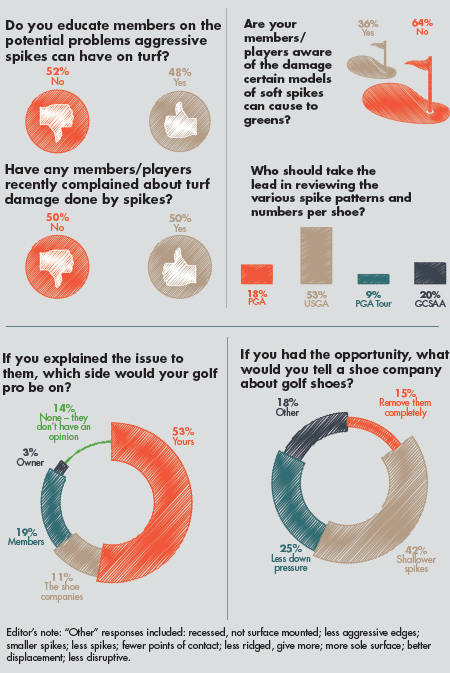

While the USGA Green Section isn’t conducting research on the effect of current shoe models on golf courses, they continue to monitor the anecdotal evidence as observed by the USGA field agronomists, says Dr. Kimberly Erusha, managing director, USGA Green Section. “The continual change in golf shoe design makes research complex,” she says. “Ultimately, it also comes down to individual facilities and golfers as they evaluate the impact of products on the quality of their putting greens.”

According to the GCSAA, the membership is aware of the situation, particularly following the PGA Merchandise Show, but the board has not had the chance to discuss the issue.

Asked which organization should take the lead on reviewing various spike patterns and numbers per shoe, 53 percent of respondents said the USGA, followed by GCSAA and PGA at 20 percent and 18 percent, respectively, “If some of the bigger clubs and the USGA did put some information out there that this is causing a negative impact to the putting surface and playability, I think people would start to listen,” Rennie says.

|

Research The stance on spikesWalk on any green and you’ll see how spike technology has changed over the last two decades. The prevailing attitude from turf heads is that golf shoe spikes are getting longer, sharper, wider and more aggressive. As a result, the modern golf shoe is impacting playing conditions by damaging greens. Is it time to take a hard line against soft spikes? We asked GCI readers what they thought and this is how superintendents responded to some key questions on this issue. In February, GCI created and facilitated a survey vie the online portal Survey Monkey that examined superintendent attitudes toward modern golf cleats. The survey was promoted to GCI readers via Twitter and Facebook, with 242 GCI readers responding. No incentive was offered to complete the survey. Of the respondents: 90 percent were turf professionals (76 percent superintendents and 14 percent assistant superintendents); and 76 percent were from single-course facilities. — The Editors

|

Heavy metal

Metal spikes presented similar challenges to those responsible for maintaining golf course – and even clubhouses – in the 1990s. A combination of spike marks and weakened turf on greens and spike-related damage inside clubhouse facilities and locker rooms led to widespread metal spike bans in the 1990s. Some superintendents say the industry is approaching a similar crossroads – albeit without the clank produced by metal spikes.

Metal spikes presented similar challenges to those responsible for maintaining golf course – and even clubhouses – in the 1990s. A combination of spike marks and weakened turf on greens and spike-related damage inside clubhouse facilities and locker rooms led to widespread metal spike bans in the 1990s. Some superintendents say the industry is approaching a similar crossroads – albeit without the clank produced by metal spikes.

“I think the people who are engineering these shoes are smart people,” Breen says. “I think there are ways to engineer shoes to reduce the pounds per square inch where the weight is developed on spikes that aren’t very flexible that protrude beyond the sole and bottom of the shoe. I think that is the solution – they just engineer a shoe that takes into account the quality of the putting surface. The game of golf is played on the greens. A big part of the scoring is on the greens. When you design a shoe that degrades the quality of a putting surface, you are degrading the quality of the experience and the game.”

Guy Cipriano is GCI’s assistant editor.

Explore the March 2015 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Audubon International announces newest leadership appointees

- Southern golf trifecta

- Sports for Nature Framework gains new signatories

- Camiral Golf & Wellness upgrades Stadium Course

- Troon selected to manage The University Club of Milwaukee

- Kafka Granite adds new business development manager

- GCSAA celebrates 10-year anniversary of collaboration with Congress

- DLF launches new seed enhancement solution