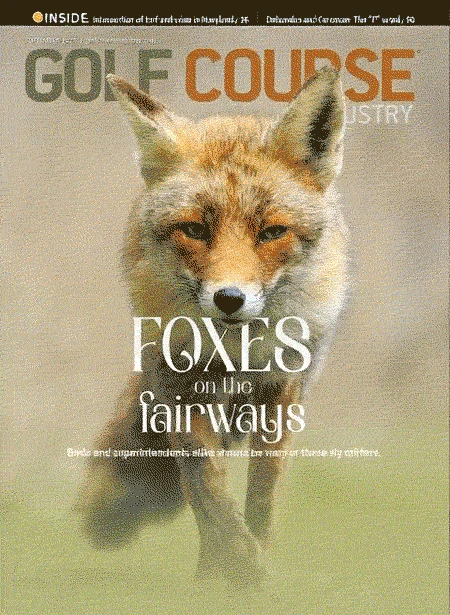

The sight of two little baby red foxes prancing around a course, wrestling with each other might seem harmless, but when these kits begin to dig holes on the greens wide enough to fit an arm, the course’s playability is jeopardized.

When David Vetrovec started as the new superintendent at Madison Parks’ Glen Golf Course, a public 9-holer in Madison, Wisconsin, the presence of foxes was not unusual.

“The foxes would dig in the bunkers, and it wasn’t a tremendous issue,” he says. “It wasn’t anything that we tried to deal with or deter. … We lived with it.”

Now the director of golf operations for Madison Parks, Vetrovec recalls, during the former Glenway Golf Course’s renovation to The Glen, spotting a family of six foxes digging daily on the greens, even in the middle of the fourth hole.

“It would be big enough and deep enough that I could stick my entire arm down into it,” he says. “It wasn’t really sustainable for us to have to repair that day after day after day and never be able to utilize that portion of the green for placing the pin.”

Madison Parks previously helped David Drake, a professor and wildlife extension specialist, with the University of Wisconsin-Madison Urban Canid Project, a research study on urban coyotes and red foxes designed “to better understand their ecology and behavior.”

From their pre-existing relationship, Vetrovec and his team called Drake for advice for their vexing vixen problem.

“They’ve always been a very big supporter of our project, and approved our request to trap on their properties,” Drake says. “So, when they were having trouble and the golf superintendent called me, I felt obligated to help them because they’ve been such a big help to us.”

It’s a long tail

The open stretch of land dotted with trees makes golf courses a perfect replication of a savannah landscape, attracting foxes. “Urban landscapes that have kind of a matrix of open area with some woody vegetation cover like forests or shrubs and things like that,” Drake adds.

Drew Cowley, owner of Cowleys Pest Services in New Jersey, says the assortment of insects and easy access to food discarded in trash cans makes courses even more ideal places.

“They’re going to have chipmunks, they’re going to have mice, they’re going to have rabbits, they’re going to have ducks,” he says. “It’s a perfect hunting ground for the fox, and then easy pickings because humans might be feeding them or” they’re eating out of “garbage cans on every hole.”

Foxes are close relatives to dogs, and their playfulness makes them appear endearing. But Jack Ammerman, owner of Advanced Wildlife Control in Greenwich, Minnesota, advises against interacting with them.

“If it were me, whether I’m a superintendent or I’m a golfer, I would not approach it,” he says. “If the animal comes toward me, I would jump in a golf cart or quickly go the other way.”

His approach to keeping a distance is out of concern for people’s safety. “Fox is not the No. 1 carrier of rabies — that would be bats and skunks — but I think fox may be No. 3 or No. 4.”

Determining whether a fox has contracted rabies can be a challenge because, especially during the early stages of the disease, there are no noticeable symptoms besides aimless wandering.

“They’re not sure what’s going on, they will approach people and everybody looks like, ‘Oh, it’s a cute little fox and — oh, come on,’” Ammerman says. “They’ll hold up a potato chip or something, try to get it to come. Then as soon as it gets up there — Bam! They get bitten.”

It is a misconception that spotting a fox in daylight means it has rabies. “That is not necessarily the case, especially in urban areas, because urban areas, we do have red fox that are out during the day,” Drake says.

During the advanced stages of rabies, visual symptoms of drooling and salivating occur. He also adds that rabies cases among foxes aren’t very common outside the Gulf Coast.

Although a skin scrape is required to determine whether an animal has mange, visible signs of hair loss and redness can be indicators.

“You might see crusty eyes or a crusty face,” Drake says. “If the animal’s losing hair at the face, you might see open scabs or open wounds on the animal’s body as well.”

For fox sake

Cowley normally receives five to 10 calls every summer about foxes, and he recommends leaving them alone. When they come close, within 50 or even 100 feet, “Just make some noise, try to stand your ground and let them know that you’re not afraid, and they’ll typically take off.”

Ammerman handles increased calls during June, because foxes will give birth in April and May. “September-ish moms will give the boot to the young and they’ll have to go out and about,” he says. “That’s another high-profile time where you see a lot more animals.”

When it comes to spotting a fox, the visual sighting is the easiest way to tell if the course has a visitor, but their scat scattered throughout the greens can also be a sign.

“It will generally have hair in it, much like another kind of carnivore, like a coyote,” he continues, “but it would be a smaller sample, and it will have hair from mice, rabbits and things like that.”

Ammerman adds that fox den sightings also suggest the presence of foxes. These holes are about the same size as groundhog holes, but with fur and feathers surrounding their entrances. And although the holes might allude that a fox’s home is nearby, Drake says they often only visit courses, and their dens are located elsewhere.

That’s how the fox family arrived at their digs at The Glen.

“They actually lived in a neighborhood, in somebody’s yard, and then just came here,” Vetrovec says, “but [Drake] said in tracking them, that’s not the only place that they went. They would travel for miles and be in lots of open spaces.”

If superintendents want to take matters into their hands, Ammerman says there are three different types of traps that can be used. These include a heart-shaped trap that encloses animals inside, a cage trap that critters walk into, and a foothold trap that handcuffs creatures when they sniff bait or step in the wrong spot.

“There are a billion cage traps for sale at farming, tractor supply stores, and those will hold up for a very short period of time,” Ammerman says. “Professional traps are going to cost anywhere from $150 to 200. Professional cage traps and those traps will last you a lifetime.”

After choosing the right device, it’s up to the superintendent or expert to determine whether to snare the fox or let it free.

There are other ways to control foxes besides utilizing traps. “The easiest way to get that fox to move on is to shovel up some dirt in front of that fox den,” Ammerman says. “Disturb it like something’s been digging.”

Both Cowley and Ammerman agree that superintendents should contact professionals, and make sure that these experts are able to trap foxes as different states have distinct licensing protocols.

Thinking outside the fox

At The Glen, Drake discovered the family of kits weren’t forming a den with the intention of building new holes, but were rather learning how to dig.

Drake and Vetrovec worked together to establish preventative measures of strobe lights on the perimeters of the course, coyote decoys and trail cameras to pinpoint the timing of the fox activity. After trying out these tactics, they choose to live trap, radio collar and relocate the foxes. Drake doesn’t recommend relocating foxes, though: it led to a few mortalities.

“Obviously, you can treat the soil with some kind of herbicide,” he says, “but it really depends on the problem. It really is pretty situational specific and problem specific.”

The maintenance team at The Glen used plugs from the edge of the course, filling the holes with them. After the foxes were removed, Vetrovec says, they patched in the holes. Within four weeks, the repaired areas appeared the same as the other greens.

Vetrovec also credits the construction for making the restoration process simpler. “We were able to pull plugs off of there and move turf plugs into it, so we didn’t have to seed it in or anything like that.”

Three years later, The Glen’s renovation is complete. Foxes still frequent the course but are causing less damage than before. “If they’re not causing any damage, we’re perfectly happy to co-exist, us with them,” Vetrovec says.

Vetrovec advises other superintendents and directors to keep in mind the severity of damages when determining the best course of action.

“Is it something that it’s OK to live with just because of you being on their turf?” he asks. “If they’re causing damage to greens or something else, reach out to your local extension expert and see what kind of options you may have.”

Explore the September 2025 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- Foley Company hires Brandon Hoag as sales and support manager

- Advanced Turf Solutions acquires Long Island, NYC distributor

- Twin Dolphin Club earns Audubon International certification

- Carolinas GCSA supports Col. John Morley Centennial Campaign

- GCSAA announces 2025 Dr. James Watson Fellows

- Tartan Talks 115: Chris Wilczynski

- 2026 Excellence in Mentorship Awards: Brian Bossert

- Redexim Launches Turf-Tidy 5000