Kelly Grow almost never worried about insects during his 26 years at Hidden Valley Country Club in Sandy, Utah. Part of that happy ignorance was because he started as a “bunker kid” and worked his way up the maintenance team ladder to assistant superintendent, seldom if ever making the call about what and when to spray. And part of that is because the club, located about 20 miles south of downtown Salt Lake City, was blissfully free of most insects.

“In northern Utah, insects are not a huge thing,” Grow says. “The only insect we ever really went after was the grub. That was the only one that caused damage enough that we constantly treated. You see 14 birds picking at one spot, you know you got grubs. … There was never any preventative, it was all reactionary.”

When Grow moved almost 300 miles south two years ago to become the superintendent at The Ledges of St. George, near the Beehive State’s southern border, he realized rather quickly that he needed to expand his insect insight. “I’ve dealt with billbugs, I’ve dealt with sod webworms, and now they’re warning us that nematodes are coming this direction,” he says.

Most perplexing, though, is the flea beetle.

The tiny jumping beetle prefers warm and dry weather, and St. George meets both criteria: Average highs top 80 most Mays and don’t drop back into the 70s until late October, temperatures creep into triple digits in July, and rain is normally only a rumor. They can also “wipe out bluegrass and ryegrass,” Grow says. “And that’s what I have on my fairways and my rough.”

The St. George flea beetles popped up across the region in 2016 — perhaps expelled from their native habitat thanks to recent rapid development — and remain confoundingly mysterious. Some of the region’s 18 golf courses deal with them and others have been mercifully spared for now. The easiest manner of detection is laying a sheet of white paper on the turf. And while Grow has worked with Adam Van Dyke of Professional Turfgrass Solutions to graph three distinct lifecycles and plan optimal application programs, no one has really figured out where they go during the winter.

The good news for Grow is that just two or three applications have dropped the flea beetle sample count at The Ledges from “the hundreds” last year to less than 30 this year. He started with Tetrino insecticide, designed to combat white grubs and annual bluegrass weevil, then applied a competing insecticide and another granular insecticide.

“It’s all about timing when you spray,” Grow says. “You can throw $100,000 worth of chemical down, but if you don’t do it at the right time, you’re just throwing money away. You have to know what and when to spray.”

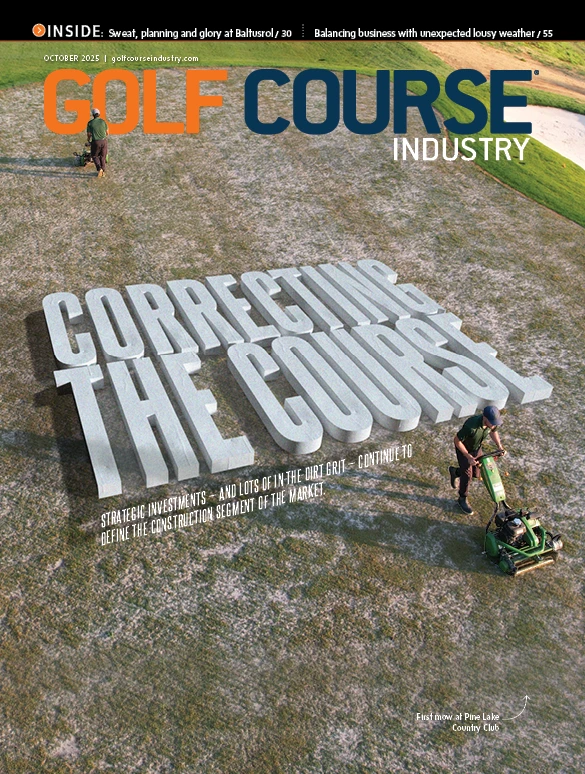

Explore the October 2025 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.