Wintertime in western Massachusetts means a lot of golf courses are closed — including Ledges Golf Club in South Hadley where Amanda Fontaine is the head superintendent. The course closes around Thanksgiving.

Appearing on the Wonderful Women of Golf podcast with host Rick Woelfel, Fontaine describes the steps she and her team take to ensure their bentgrass is healthy enough to withstand a New England winter.

“We’ll start out with verticutting our greens,” she says, “getting a good aeration on them afterwards, and then topdress on top of that. And then after that, we’ll pretty much go into winter with a winterkill spread and some regulation, get through the winter with that and protect the turf with fungicide.

“After that, we’ll go with a nice, heavy topdressing to really protect the plant as much as possible. We try to keep the aeration holes open as much as possible for drainage. Because we don’t get that huge, heavy snow cover every winter, that’s always a big problem.”

Fontaine’s ideal winter — as it would be for her peers — would feature a consistent snow cover. Her biggest concern during the winter months is ice. “Ice is a big enemy,” she says. “It really limits the amount of oxygen the plant can get. We keep a good timeline of when we get ice and when to take it off. Hopefully, Mother Nature takes care of that for us. But if it gets to that scary point where it’s getting close to that 45-day mark of ice cover, then we have to go out and take preventative measures.”

The Ledges is 20 minutes from the University of Massachusetts campus in Amherst. UMass, along with the University of Minnesota, is involved in an ongoing winterkill study.

When Fontaine assumed her post five years ago, she found herself immediately confronting winterkill issues.

“[My first season] was a huge winterkill season,” she says, and the next season as well. I saw the benefits [of the study] right away.”

The program involves Fontaine and her team installing solar-powered, GPS-driven nodes at various depths on putting surfaces to measure such things as oxygen, moisture and CO2 levels.

“We can determine these factors at three different depths,” Fontaine says. “I believe it’s 2, 3 and 6 inches. So, we can really tell what’s going on at all different depths of the soil profile.”

Modern technology allows Fontaine to continuously monitor soil conditions through the worst of the winter weather.

“I can log on and tell exactly what’s going on in the soil,” she says. “I know what the temperature is in the soil, I know how much oxygen it’s getting, how much CO2 the plant is giving off. So, I pretty much know when respiration happens and at what levels it’s going on.”

Fontaine says having this kind of information at her disposal is an asset when dealing with customers.

“It’s been super helpful, especially when communicating with the golfers and the public as to why we’re closing when we close, why frost delays are important, and why staying off the turf when the ground is frozen. It helps to be able to have specifics to present the information to the membership and especially presenting it to the town because we are a municipal golf course.”

Fontaine has the ability to connect with other golf facilities and learn how they are coping with winter.

“I can log on and if anyone in the country or in other countries has a node, I can look at their data and see where we are in comparison to different climates,” she says. “There’s a bunch in my neck of the woods up here that gave nodes around their golf courses so I can compare within 10 miles of my own golf course, or around the country as well.”

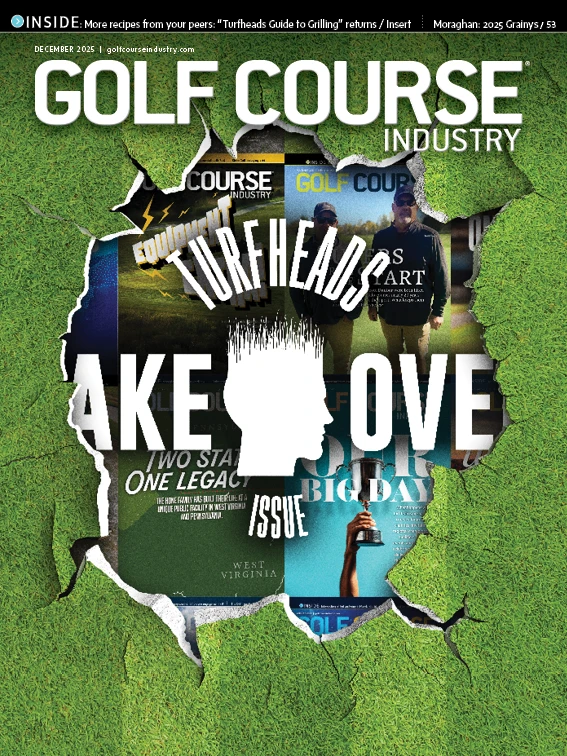

Explore the December 2025 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Golf Course Industry

- The Aquatrols Company launches redesigned website

- 2026 Excellence in Mentorship Awards: Justin Sims

- Foley Company hires Brandon Hoag as sales and support manager

- Advanced Turf Solutions acquires Long Island, NYC distributor

- Twin Dolphin Club earns Audubon International certification

- Carolinas GCSA supports Col. John Morley Centennial Campaign

- GCSAA announces 2025 Dr. James Watson Fellows

- Tartan Talks 115: Chris Wilczynski